Panhard bare cylinder isn't tapered (updated)

Friday 02 November 2012 Filed in: Blog Comments

I have long said that boring a tapered liner is extremely difficult, and I often wondered how Panhard did it, but today I found out for sure.

I have measured the internal diameters of a bare aluminium cylinder casting, and it is truly parallel internally. I have also measured a new old stock liner and this was parallel internally and externally, so it was suggested by me, that Panhard machined a tapered liner was the stuff of legends or folklore.

I actually surprised myself by accidentally stumbling upon a method of boring a tapered liner the other day, and although I might still do this using the boring bar directly, I didn’t think this is what Panhard did, as it’s not really a production method. So how else could this be achieved?

It was possible that Panhard used a tapered honing process, but again it’s way too slow and therefore probably not what Panhard did either.

I knew the cylinder finning and casting were tapered, and I wondered whether this fact was lost in translation when the cylinder was being described in the press releases, but then I had my eureka moment and I discovered an even easier way. I was drawing up a new cylinder in CAD looking at the original casting, and taking measurements, when it hit me.

The answer lies in the liner or sleeve is an interference fit in the cylinder casting, and depending on the interference, the strength of the cylinder casting (thickness of the walls) this determines how much the liner distorts, this distortion is what tapers the cylinder bore.

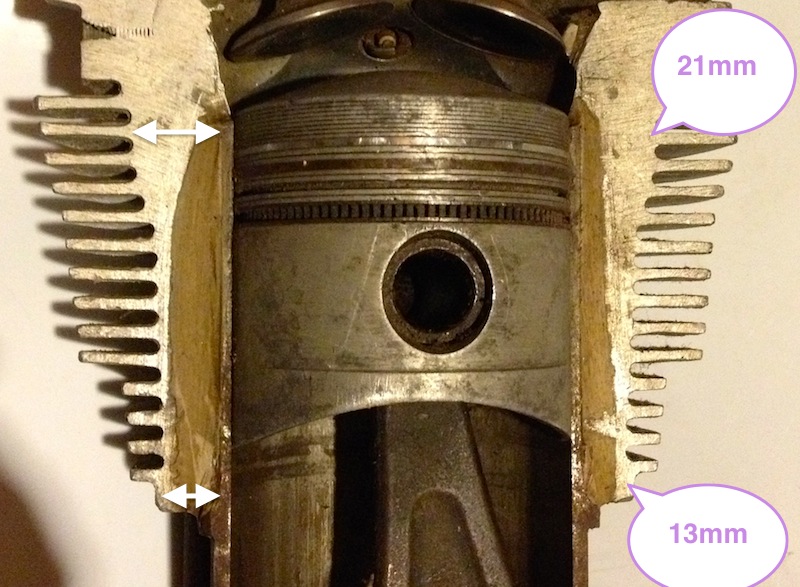

When the bare cylinder is warmed up the interference fit is lost, and the cold liner or sleeve is “dropped” in place, but when it cools the cylinder starts to squeeze the liner. However the cylinder walls have different thicknesses tapering from the bottom of the liner to the top, as in the picture below.

What this means is for a given interference fit along its length, the liner will be squeezed more at the top than the bottom, because the cylinder is much stiffer in compression at the top, and less stiff as the liner moves away from the top. The reality is on a cold bore today when it was 4ºC, the diameters measured across the liner from top to bottom are as shown.

3.3604” at the very top (closest to the combustion chamber in the above photo)

3.3620” in the middle of the liner, measured roughly in the middle of the cylinder casting.

3.3626” in the liner, measured at the base of the cylinder casting.

Lastly, at the base of the liner skirt, which is the bit that isn’t contained by the cylinder casting, that is where the spigot goes into the crankcase, the actual machined bore diameter of 3.3670” is seen again on the micrometer.

There is a 0.007” variation on a cold cylinder from top to bottom, and no wonder people often said some engines were quiet and slow running, until they warmed up slightly!

The mystery as to how the cylinder bore becomes tapered is finally solved for me at least, and possibly a few others too.

It also means you can parallel bore the cylinder casting or sleeve, and you will not destroy the factory taper, but you must always take the liner or sleeve out of the cylinder casting otherwise you will.

If you make a larger bore engine using the standard cylinder casting & original interference fit, you will reduce the taper effect at the top, because you have reduced the wall thickness and compressive stiffness pro rata.

I am almost ready to machine the cylinders to suit the new pistons, but I need to explore a couple of other things first, namely how perpendicular is the bore, and how does the cylinder bore change with temperature versus the piston crown & ring body, which will establish the actual bore size required for the liner or sleeve.

UPDATE Saturday 3 November 2012

It seems that at about a cylinder temperature of 120ºC the bore is truly parallel, and approximately 0.007” larger at the combustion chamber end of the liner, than when it is cold.

I have measured the internal diameters of a bare aluminium cylinder casting, and it is truly parallel internally. I have also measured a new old stock liner and this was parallel internally and externally, so it was suggested by me, that Panhard machined a tapered liner was the stuff of legends or folklore.

I actually surprised myself by accidentally stumbling upon a method of boring a tapered liner the other day, and although I might still do this using the boring bar directly, I didn’t think this is what Panhard did, as it’s not really a production method. So how else could this be achieved?

It was possible that Panhard used a tapered honing process, but again it’s way too slow and therefore probably not what Panhard did either.

I knew the cylinder finning and casting were tapered, and I wondered whether this fact was lost in translation when the cylinder was being described in the press releases, but then I had my eureka moment and I discovered an even easier way. I was drawing up a new cylinder in CAD looking at the original casting, and taking measurements, when it hit me.

The answer lies in the liner or sleeve is an interference fit in the cylinder casting, and depending on the interference, the strength of the cylinder casting (thickness of the walls) this determines how much the liner distorts, this distortion is what tapers the cylinder bore.

When the bare cylinder is warmed up the interference fit is lost, and the cold liner or sleeve is “dropped” in place, but when it cools the cylinder starts to squeeze the liner. However the cylinder walls have different thicknesses tapering from the bottom of the liner to the top, as in the picture below.

What this means is for a given interference fit along its length, the liner will be squeezed more at the top than the bottom, because the cylinder is much stiffer in compression at the top, and less stiff as the liner moves away from the top. The reality is on a cold bore today when it was 4ºC, the diameters measured across the liner from top to bottom are as shown.

3.3604” at the very top (closest to the combustion chamber in the above photo)

3.3620” in the middle of the liner, measured roughly in the middle of the cylinder casting.

3.3626” in the liner, measured at the base of the cylinder casting.

Lastly, at the base of the liner skirt, which is the bit that isn’t contained by the cylinder casting, that is where the spigot goes into the crankcase, the actual machined bore diameter of 3.3670” is seen again on the micrometer.

There is a 0.007” variation on a cold cylinder from top to bottom, and no wonder people often said some engines were quiet and slow running, until they warmed up slightly!

The mystery as to how the cylinder bore becomes tapered is finally solved for me at least, and possibly a few others too.

It also means you can parallel bore the cylinder casting or sleeve, and you will not destroy the factory taper, but you must always take the liner or sleeve out of the cylinder casting otherwise you will.

If you make a larger bore engine using the standard cylinder casting & original interference fit, you will reduce the taper effect at the top, because you have reduced the wall thickness and compressive stiffness pro rata.

I am almost ready to machine the cylinders to suit the new pistons, but I need to explore a couple of other things first, namely how perpendicular is the bore, and how does the cylinder bore change with temperature versus the piston crown & ring body, which will establish the actual bore size required for the liner or sleeve.

UPDATE Saturday 3 November 2012

It seems that at about a cylinder temperature of 120ºC the bore is truly parallel, and approximately 0.007” larger at the combustion chamber end of the liner, than when it is cold.

Panhard bare cylinder isn't tapered

Saturday 15 September 2012 Filed in: Blog Comments

Panhard liners have had tapered bores since the early days. However when it’s time to rebuild them, I never found this out.

It was assumed by others, and I had no reason to question whether the liner was tapered internally, or perhaps the aluminium cylinder itself? The reasoning behind this was, if the aluminium cylinder was slightly narrower at the combustion chamber end, it would squeeze the sleeve and so make it tapered.

Yesterday, I got a Tesa three point bore micrometer in the post, and I was finally able to measure the internal bore of the aluminium cylinder.

I measured the bottom, middle and top of the bore of the bare aluminium cylinder, that’s without a liner or sleeve being fitted.

The divisions of the micrometer are 0.0002” or 2/10ths of a thou. There is no taper on the bare cylinder, so thats’s another bit of folklore or legend out of the way, and the only other way to achieve this would be to make the internal sleeve or cast iron liner taper outwards at the top, so that when it is inserted in the heated cylinder, upon cooling it compresses slightly more at the top than the bottom. Next up is to measure a few sleeves or liners and check whether this was done.

Interestingly the days of tapered bores were numbered with improvements in aluminium piston alloys and better machining, and Panhards have bigger issues with their piston design, so obsessing about having a tapered bore is rather irrelevant and futile.

UPDATE 23 September 2012

I measured the matching sleeve, taken from the aluminium cylinder above, and the external diameters are truly parallel, so I now know I will not have any issues when I bore the cylinder liner or sleeve.

It was assumed by others, and I had no reason to question whether the liner was tapered internally, or perhaps the aluminium cylinder itself? The reasoning behind this was, if the aluminium cylinder was slightly narrower at the combustion chamber end, it would squeeze the sleeve and so make it tapered.

Yesterday, I got a Tesa three point bore micrometer in the post, and I was finally able to measure the internal bore of the aluminium cylinder.

I measured the bottom, middle and top of the bore of the bare aluminium cylinder, that’s without a liner or sleeve being fitted.

The divisions of the micrometer are 0.0002” or 2/10ths of a thou. There is no taper on the bare cylinder, so thats’s another bit of folklore or legend out of the way, and the only other way to achieve this would be to make the internal sleeve or cast iron liner taper outwards at the top, so that when it is inserted in the heated cylinder, upon cooling it compresses slightly more at the top than the bottom. Next up is to measure a few sleeves or liners and check whether this was done.

Interestingly the days of tapered bores were numbered with improvements in aluminium piston alloys and better machining, and Panhards have bigger issues with their piston design, so obsessing about having a tapered bore is rather irrelevant and futile.

UPDATE 23 September 2012

I measured the matching sleeve, taken from the aluminium cylinder above, and the external diameters are truly parallel, so I now know I will not have any issues when I bore the cylinder liner or sleeve.

Panhard Engine Dyno Curves

Friday 24 August 2012 Filed in: Panhard Dyno

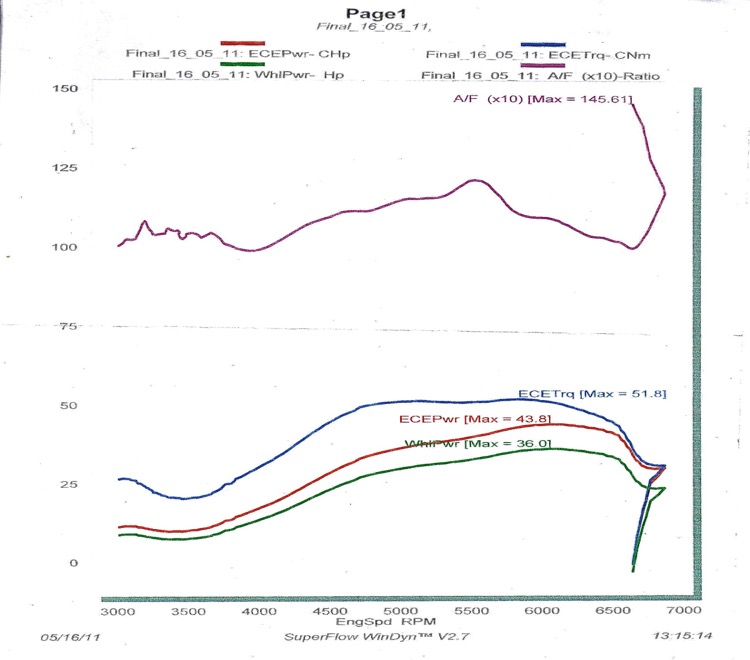

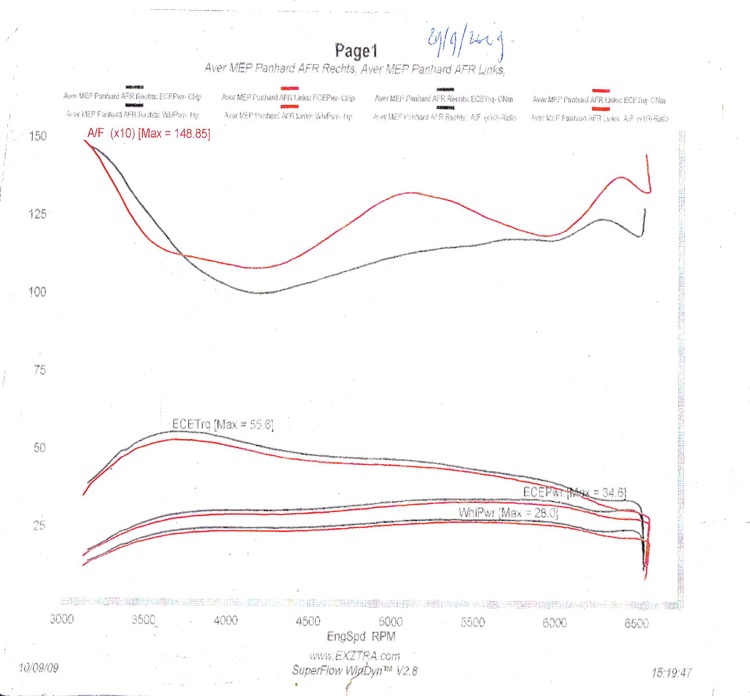

I had a nice telephone conversation the other day with a Belgian guy, who has forwarded on a few dyno curves from his engines and the Don Racine Panhard engined Aardvark special.

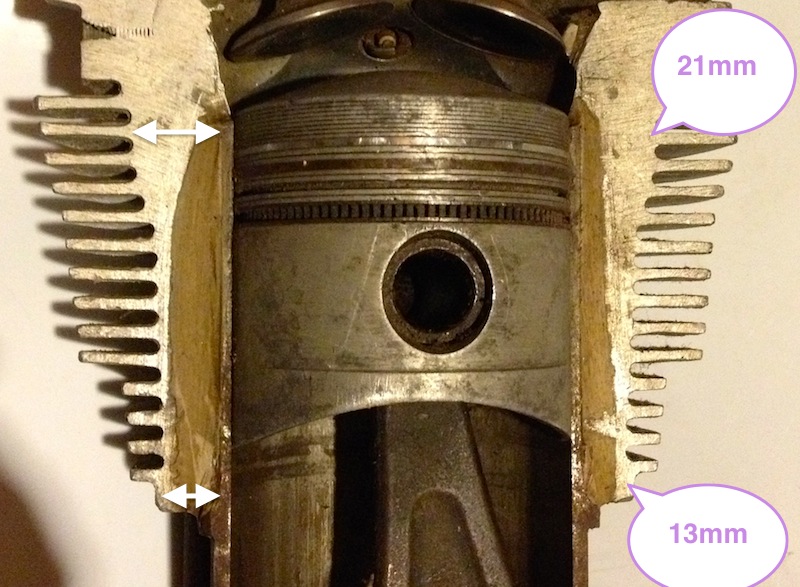

i have posted them here as a reference. I will add a few comments later, but for this Gawski tuned example, the upper curve is the Fuel/Air ratio, whereas the bottom three, are Engine Torque (calculated), Engine Horsepower(calculated), and Front Wheel Horsepower respectively.

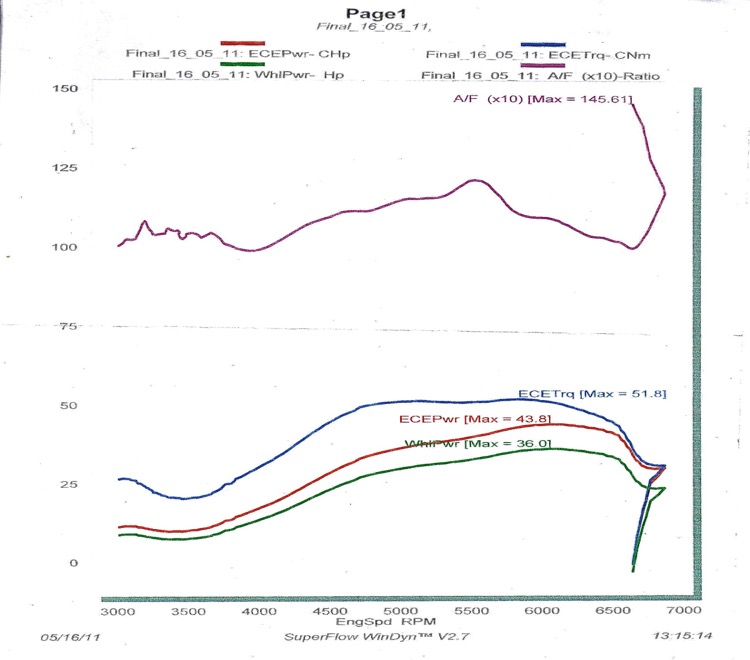

A standard MEP with a single Zenith NDIX carburettor, possibly a standard Tigre set up?

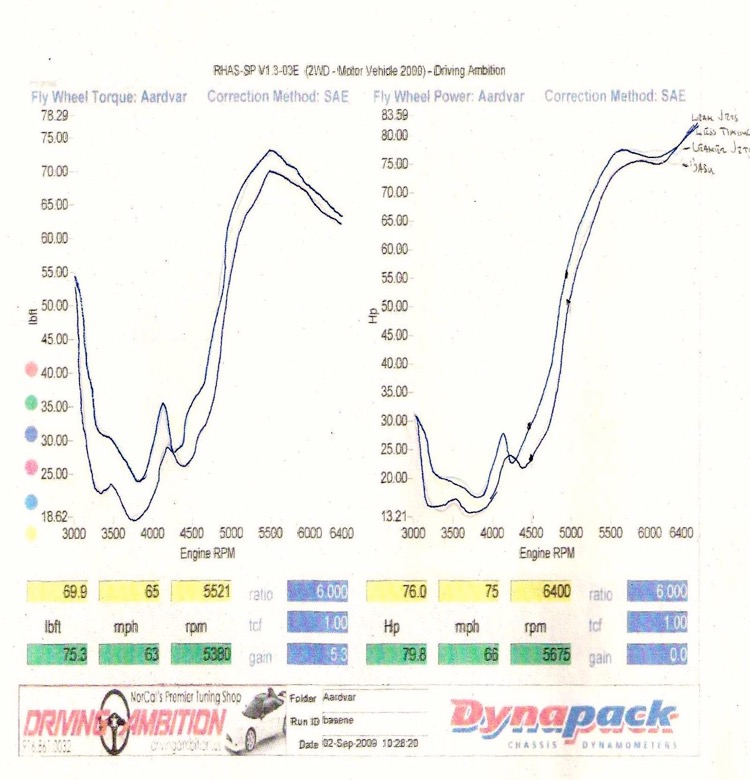

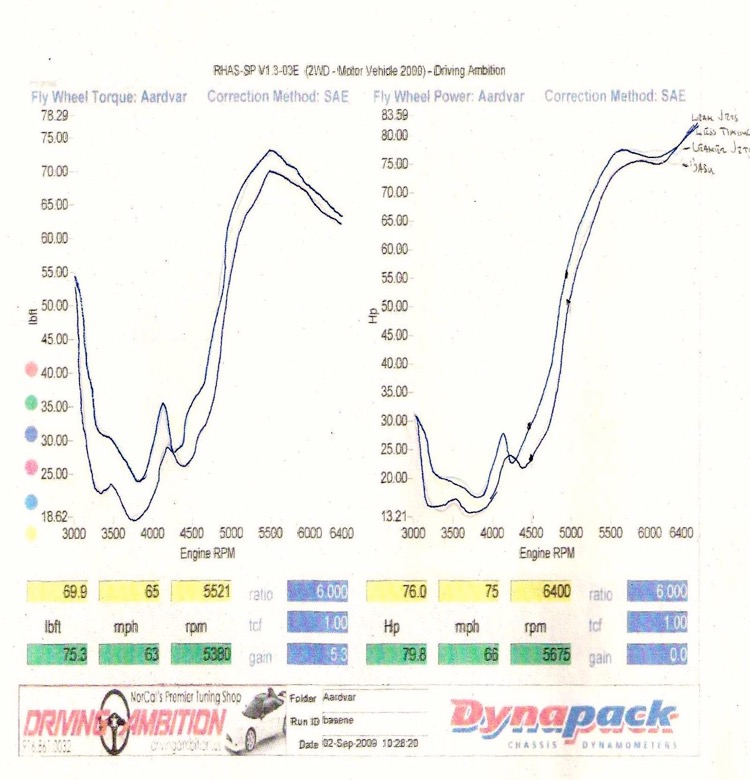

The Don Racine Aardvark example

The horsepower numbers do not really matter unless they are on the same dyno, but the shape of the Torque curves is interesting.

i have posted them here as a reference. I will add a few comments later, but for this Gawski tuned example, the upper curve is the Fuel/Air ratio, whereas the bottom three, are Engine Torque (calculated), Engine Horsepower(calculated), and Front Wheel Horsepower respectively.

A standard MEP with a single Zenith NDIX carburettor, possibly a standard Tigre set up?

The Don Racine Aardvark example

The horsepower numbers do not really matter unless they are on the same dyno, but the shape of the Torque curves is interesting.

Panhard piston first batch delivered

Thursday 19 July 2012 Filed in: Panhard Piston

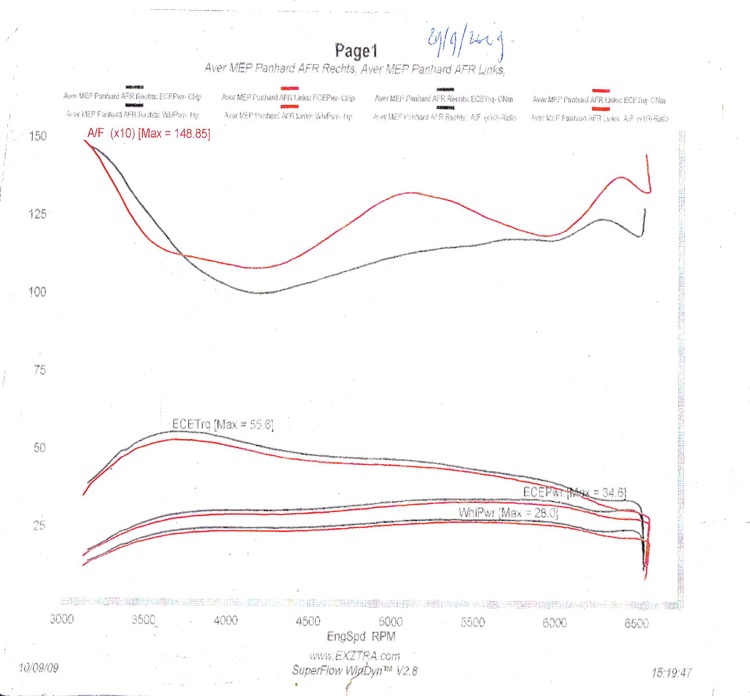

The pistons were delivered the other day, and here is the first picture of the bare piston, and below this another with the old piston for reference.

More pictures to follow, once I get back from my bike trip.

More pictures to follow, once I get back from my bike trip.

Panhard front pulley kit

Sunday 08 July 2012 Filed in: Panhard Parts

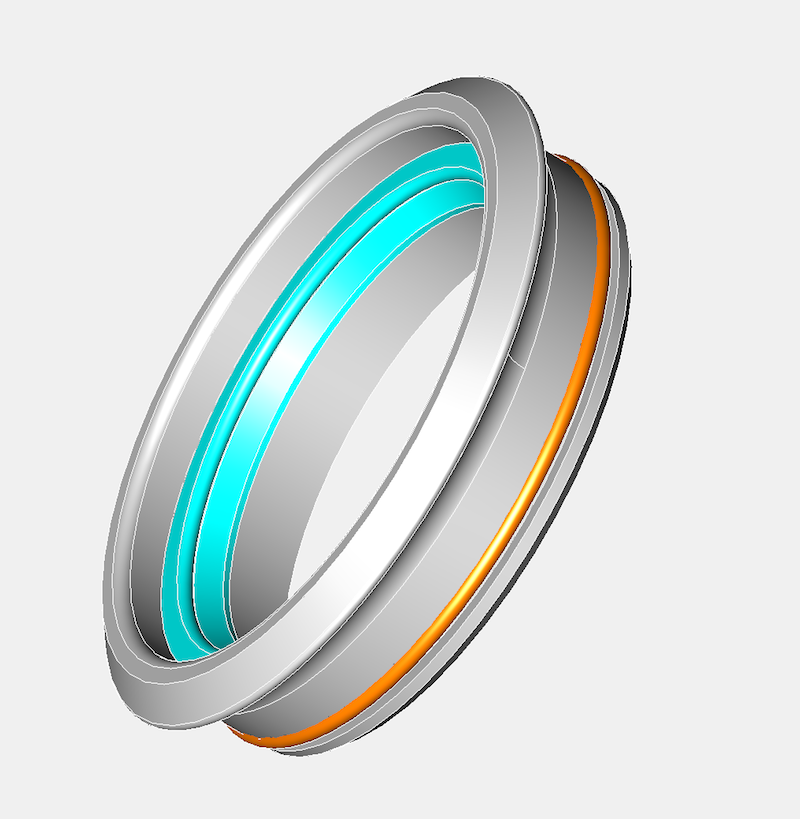

I sent a few links off to a few people and from their feedback and just to avoid any confusion, the new front pulley kit will only work with a revised seal arrangement. To update the seal you need to fit these components, which will be available assembled or as separate parts for future maintenance if required.

However, as the space available is limited within the OEM timing gear cover, the front pulley kit and the seal kit are designed to be an easy fit upgrade option, which is much the same philosophy as the filter kit upgrades, and an added bonus for those that are not removing the engine or doing additional works in this area. Initially fitting this kit might seem daunting at first, but it is really designed to be as foolproof as possible.

Obviously when the parts are made, I will post a video outlining the installations and use in situ photographs covering the assembly procedure.

ASSEMBLY PROCEDURE

First remove the old pulley after removing the fan and saving all the springs and wooden blocks. Leaving the timing gear cover in place, install the inner part of the pulley, which will consist of an aluminium centre and a steel inner ring already assembled together, engaging the key in the slot.

Next place the lightly oiled seal assembly, which will come ready assembled, over the timing gear front pulley aperture, and slide the seal over the inner ring until the steel ring is against the timing gear cover. The stainless steel ring should just be inside the opening, and now needs pressing into place.

Using the crankshaft front pulley bolt, and a spacer, press the seal assembly into position, by tightening the crankshaft bolt until the stainless steel seal adaptor is fully seated against the timing gear cover. The interference fit should be enough of an oil tight arrangement, but there is an O ring seal detail to make sure it is.

Remove the front pulley crankshaft bolt & spacer, and then place remaining part of the front pulley kit, which will be a sliding fit, into the steel inner ring. Next fit all the springs, wooden blocks, and other fan related parts and rebuild the fan assembly, not forgetting the V belt. Then refit the crankshaft pulley bolt and tighten to OEM torque figures.

Note, there is a dowel pin detail that aligns the front pulley in a set position, which will be used for those owners that want to fit a trigger wheel, whose primary purpose is to facilitate the use of third party ignition or modern engine management systems to their vehicle.

However, as the space available is limited within the OEM timing gear cover, the front pulley kit and the seal kit are designed to be an easy fit upgrade option, which is much the same philosophy as the filter kit upgrades, and an added bonus for those that are not removing the engine or doing additional works in this area. Initially fitting this kit might seem daunting at first, but it is really designed to be as foolproof as possible.

Obviously when the parts are made, I will post a video outlining the installations and use in situ photographs covering the assembly procedure.

ASSEMBLY PROCEDURE

First remove the old pulley after removing the fan and saving all the springs and wooden blocks. Leaving the timing gear cover in place, install the inner part of the pulley, which will consist of an aluminium centre and a steel inner ring already assembled together, engaging the key in the slot.

Next place the lightly oiled seal assembly, which will come ready assembled, over the timing gear front pulley aperture, and slide the seal over the inner ring until the steel ring is against the timing gear cover. The stainless steel ring should just be inside the opening, and now needs pressing into place.

Using the crankshaft front pulley bolt, and a spacer, press the seal assembly into position, by tightening the crankshaft bolt until the stainless steel seal adaptor is fully seated against the timing gear cover. The interference fit should be enough of an oil tight arrangement, but there is an O ring seal detail to make sure it is.

Remove the front pulley crankshaft bolt & spacer, and then place remaining part of the front pulley kit, which will be a sliding fit, into the steel inner ring. Next fit all the springs, wooden blocks, and other fan related parts and rebuild the fan assembly, not forgetting the V belt. Then refit the crankshaft pulley bolt and tighten to OEM torque figures.

Note, there is a dowel pin detail that aligns the front pulley in a set position, which will be used for those owners that want to fit a trigger wheel, whose primary purpose is to facilitate the use of third party ignition or modern engine management systems to their vehicle.

Panhard crankshaft pulley with trigger wheel (updated)

Friday 06 July 2012 Filed in: Panhard Parts

I have updated the CAD drawing to reflect my latest thoughts. I was looking for some oil pump parts and I came across a bag of Viton single lipped seals, which I recognised as some potential front pulley piston ring alternatives I bought five years ago. These seals were bought, as a continuation of the work I did with the rear bearing support seal adaptors, as I always intended to do away with the piston ring seals at either end of the crankshaft. I only made a few of these rear bearing adaptors, and I personally fitted a couple, and then sent some to the Netherlands, as well as a drawing to Germany.

There isn’t a seal that will fit directly into the timing gear cover, as it is a peculiar & unique diameter, so the idea back then was to make a carrier for the seal that would interface into the existing timing gear cover (same idea as the rear system I designed), which had the added bonus of not damaging the OEM timing cover too.This approach does mean a new front pulley assembly will be required, but this is in line with my philosophy of not damaging OEM stock when creating modified components. All the wearing surfaces are also easily replaced in years to come, and readily sourced, plus this system can recover worn timing covers.

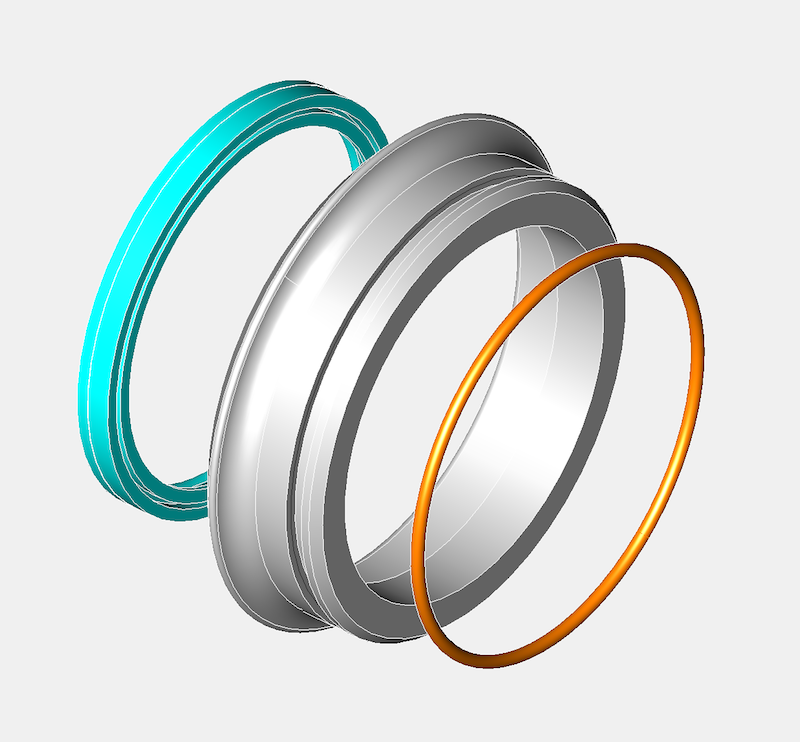

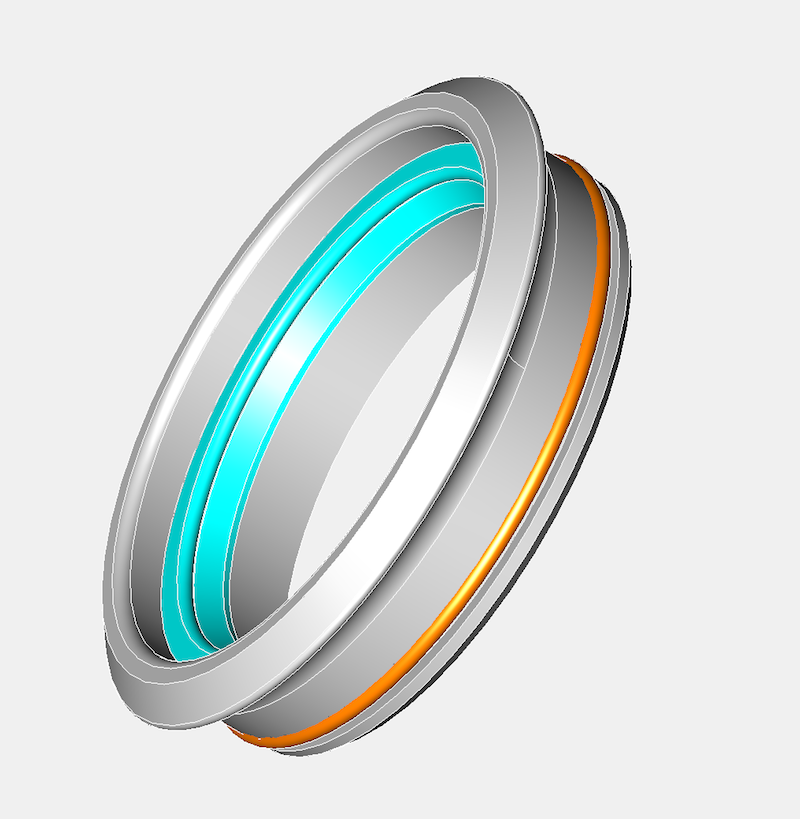

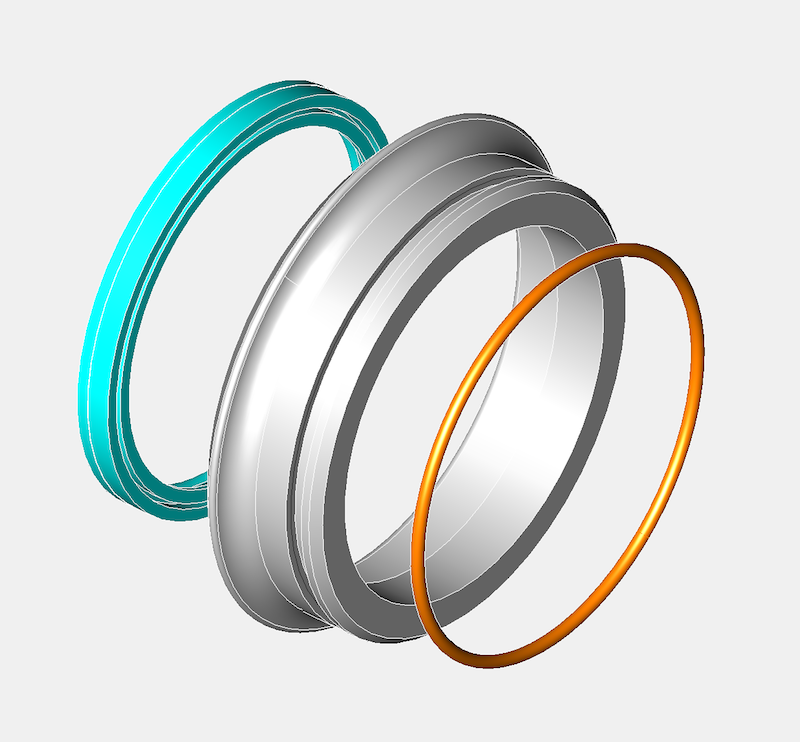

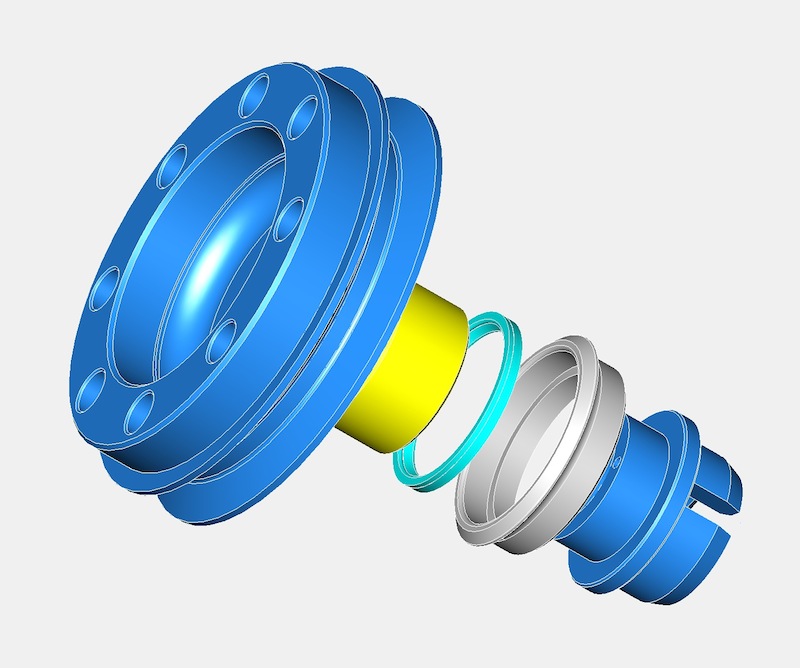

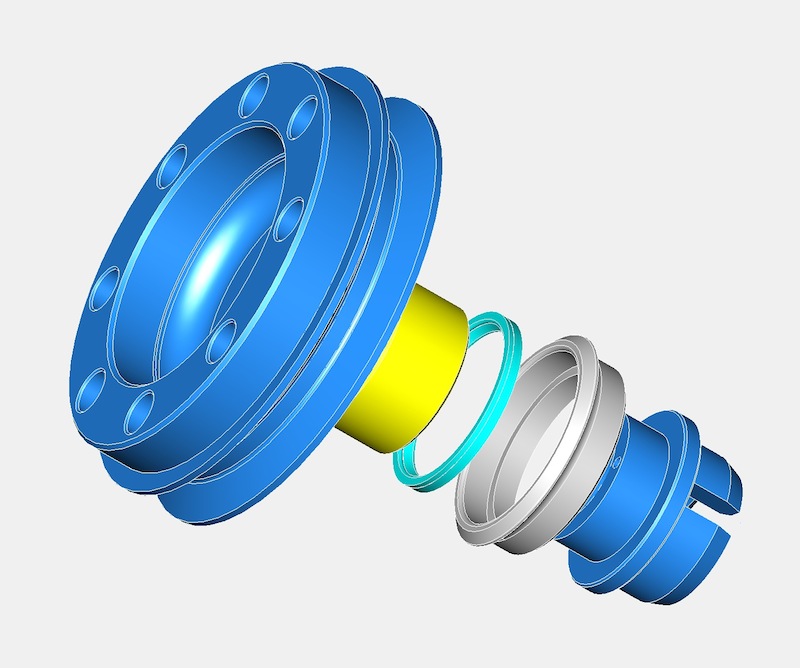

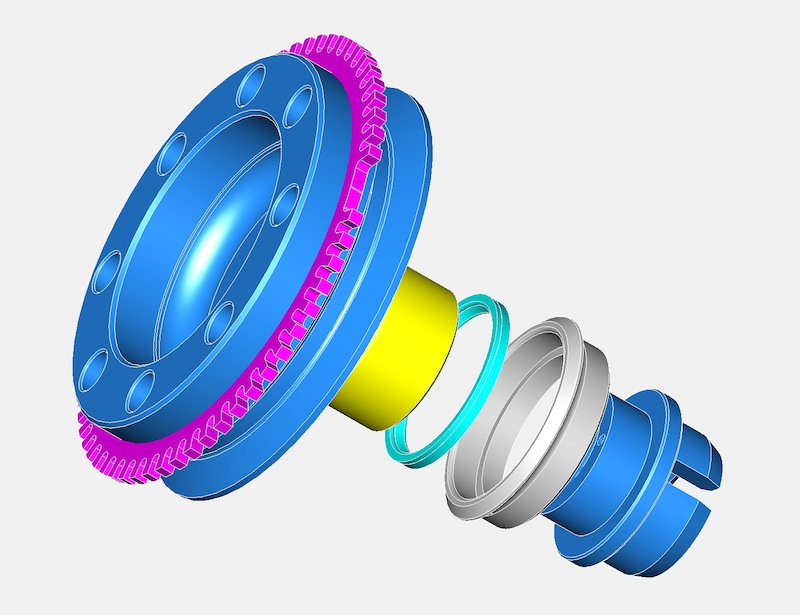

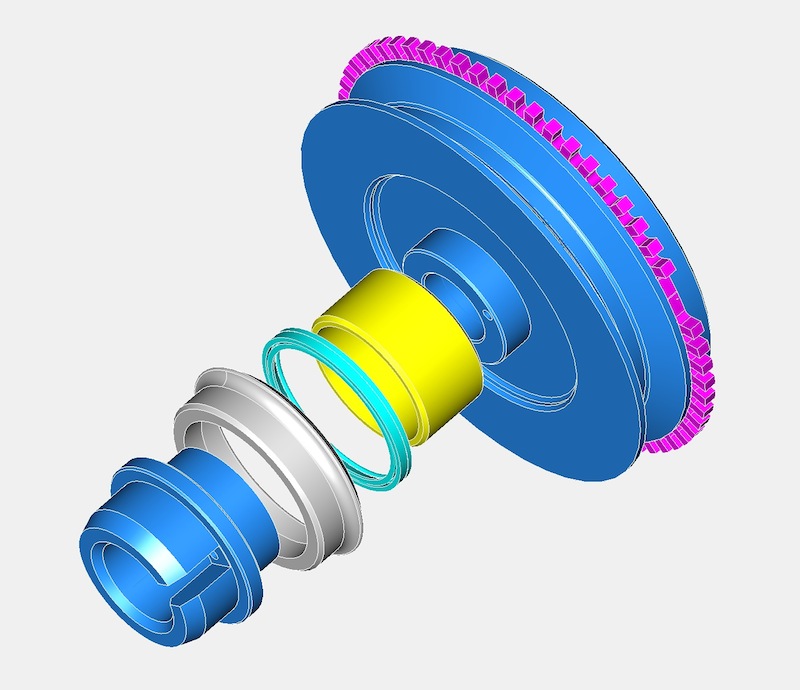

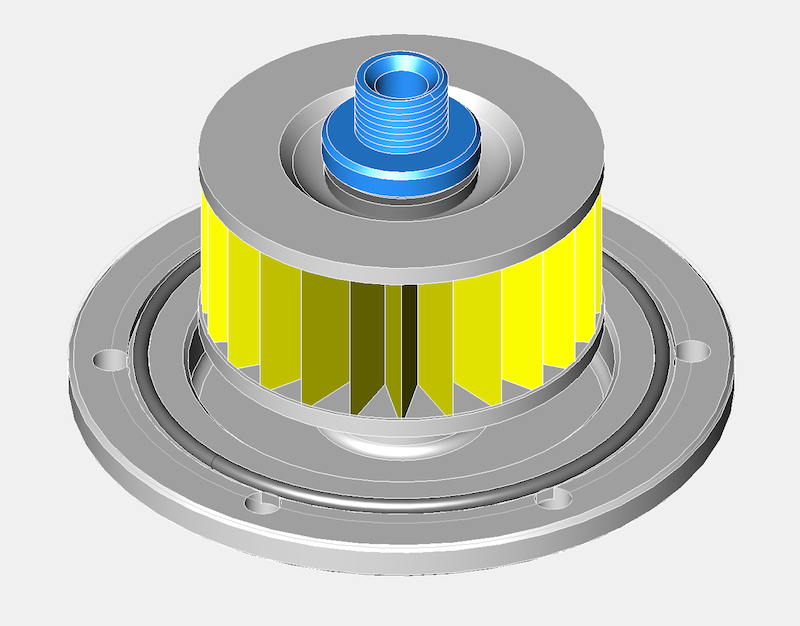

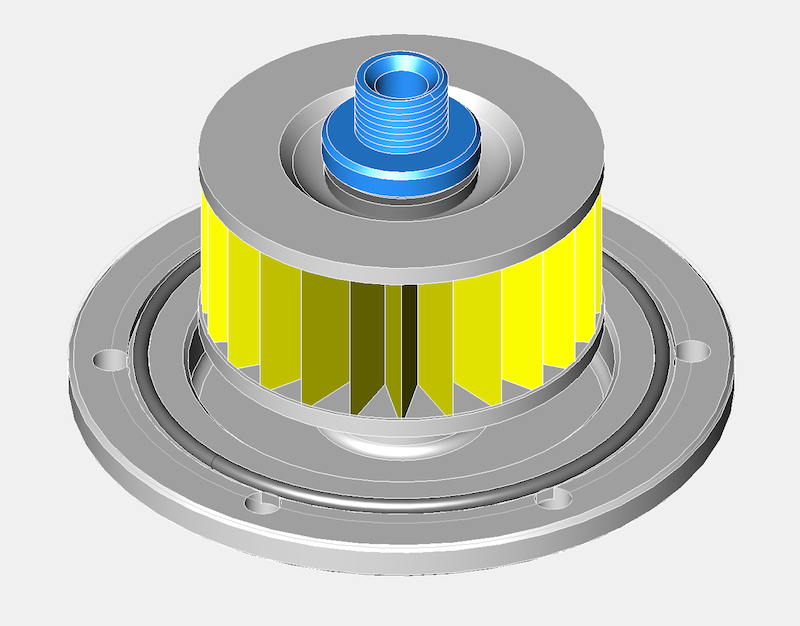

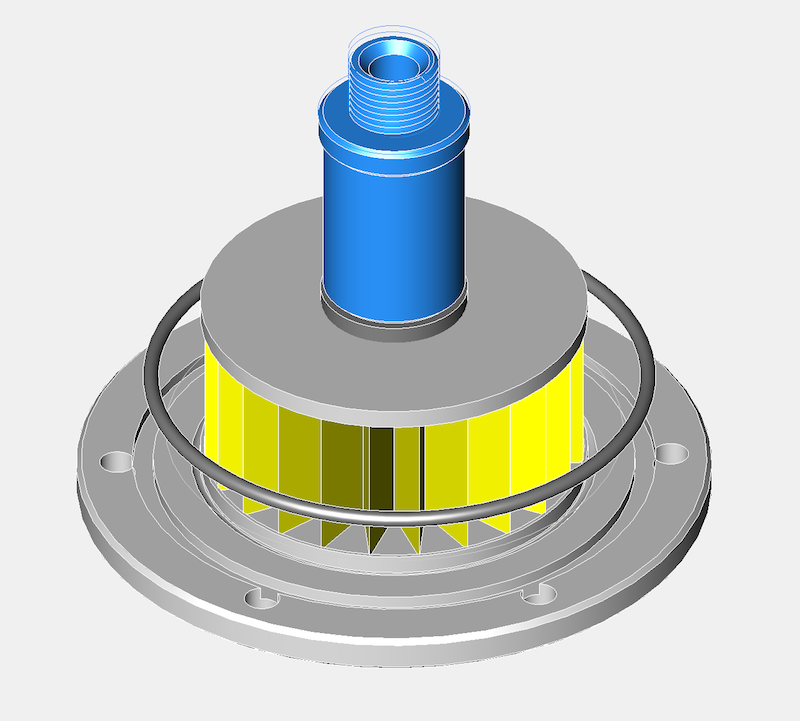

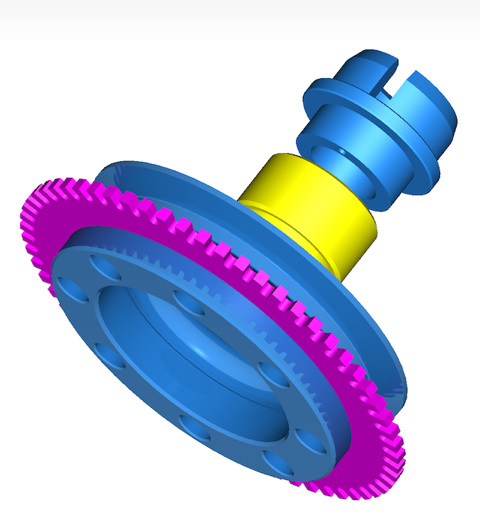

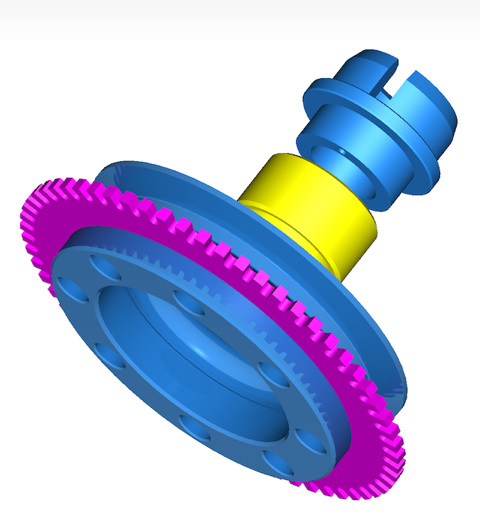

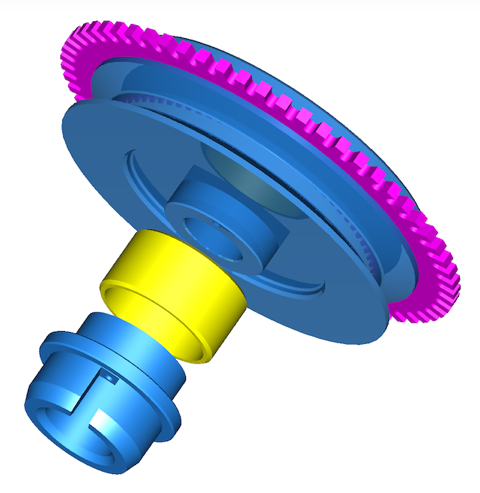

Today, I managed to get the timing gear cover seal diameter surfaces measured on a Elaton Coordinate Measuring Machine, so I now have a very precise idea of what diameter I need to make the new part so that it has a nice interference fit. This is the complete crankshaft conversion kit assembly pictured below.

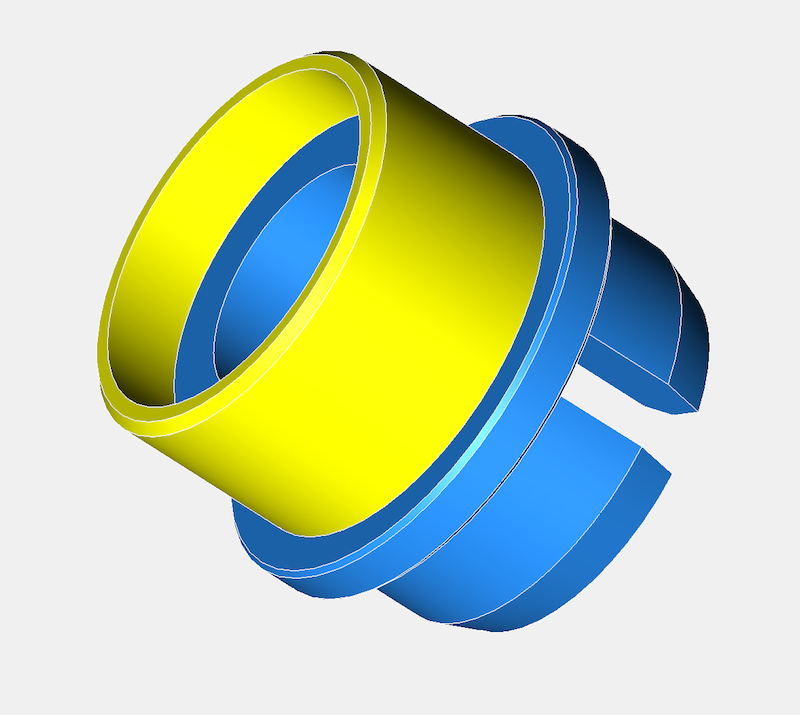

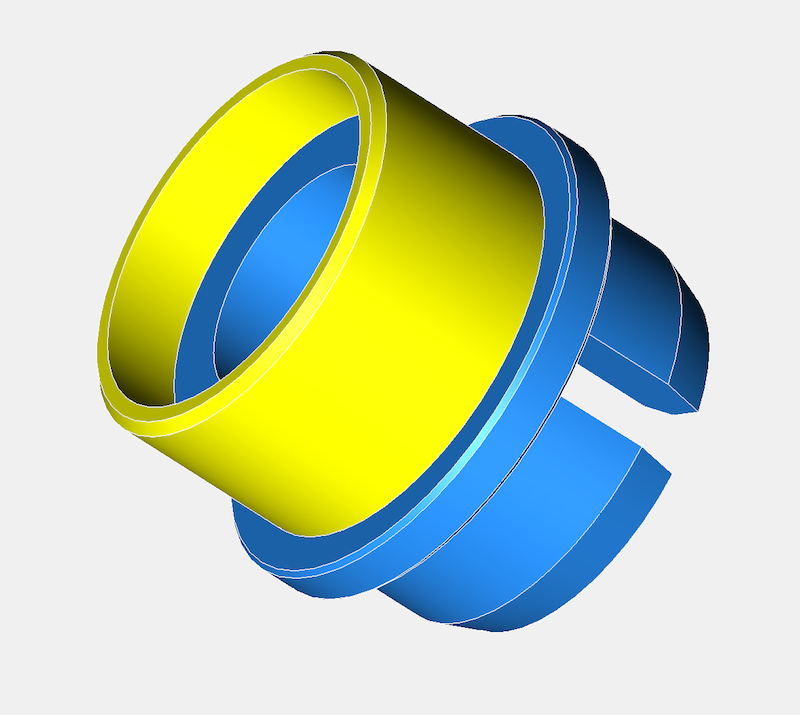

The grey part is the stainless steel seal carrier, and the cyan part the Viton seal. The yellow part is the steel inner ring, which is easily renewed if required, with the blue parts being the aluminium two piece front pulley components. These are located with a small dowel pin, however the parts are held together by the main front pulley crankshaft bolt.

It is necessary to make the parts this way to allow for DIY installations by Panhard owners, and it will be relatively straight forward to fit the conversion kit.

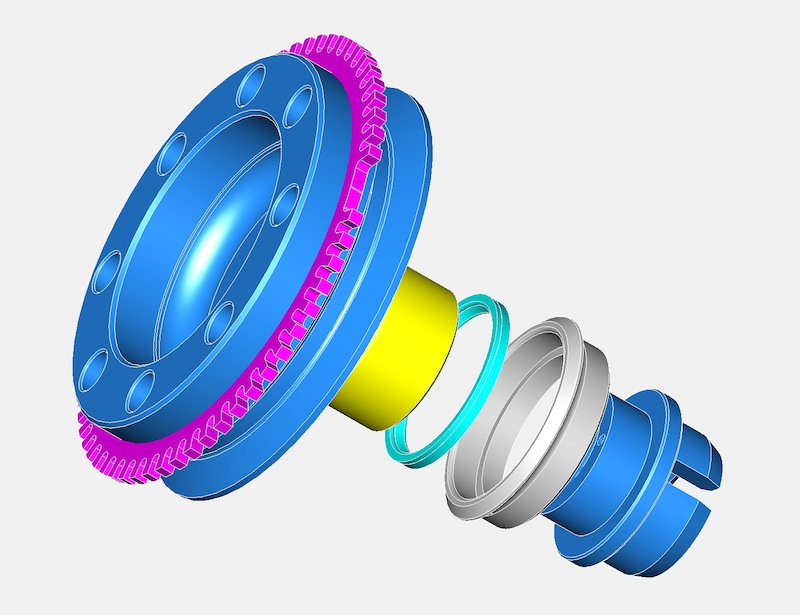

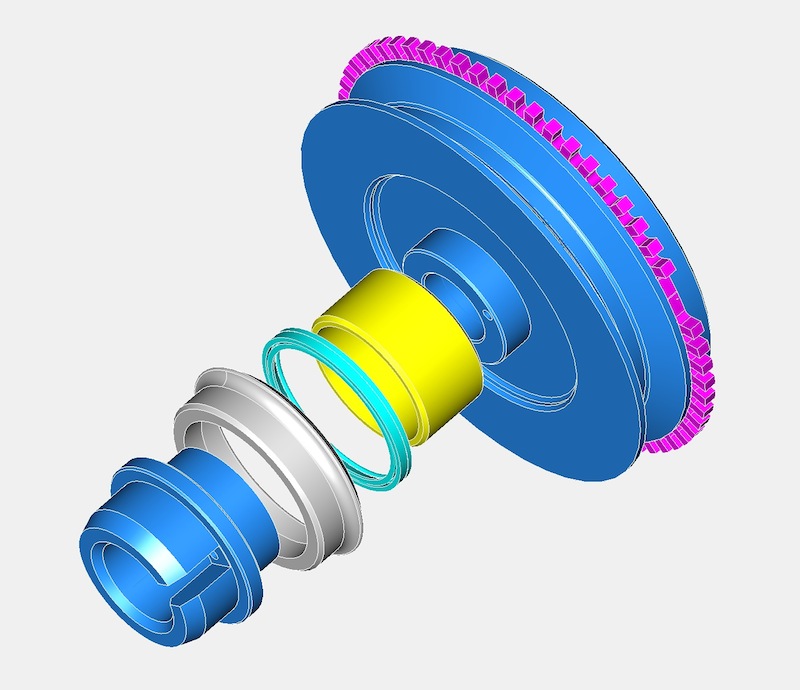

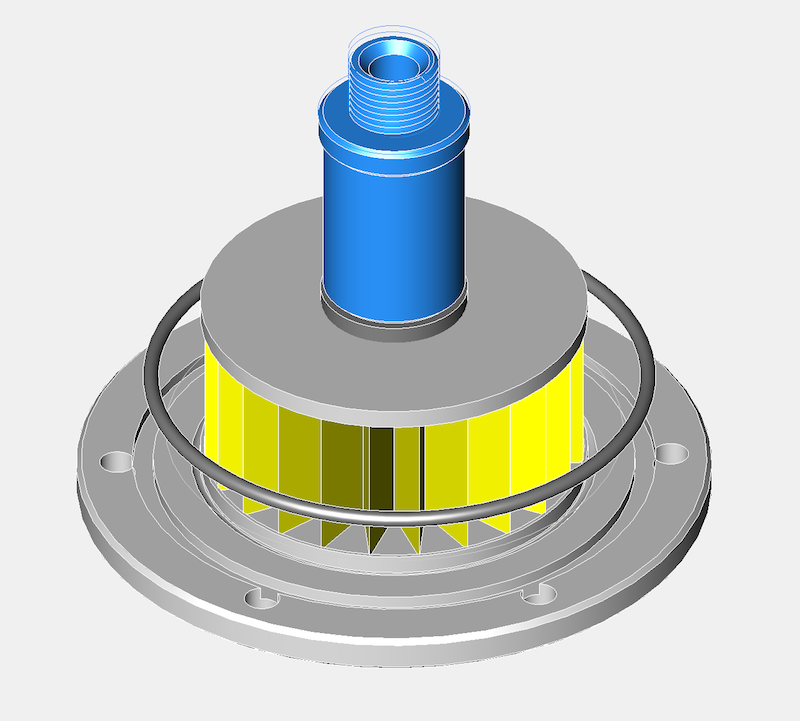

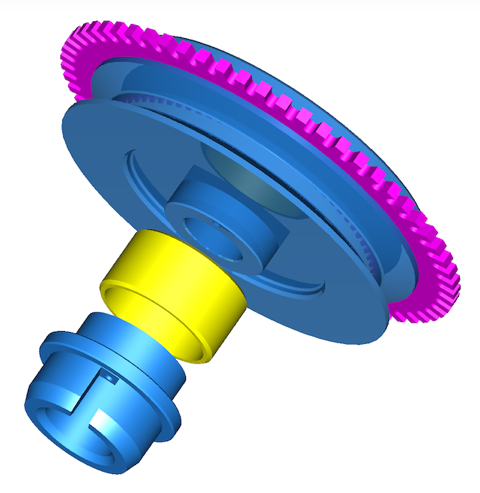

The picture below shows the optional trigger wheel version, which is needed by modern ignition or engine management systems, but fitting these is not for the faint hearted!

There are different tooth patterns available, but the one in the picture above is a 60-2 trigger wheel, commonly used by Bosch for VAG engines.

There isn’t a seal that will fit directly into the timing gear cover, as it is a peculiar & unique diameter, so the idea back then was to make a carrier for the seal that would interface into the existing timing gear cover (same idea as the rear system I designed), which had the added bonus of not damaging the OEM timing cover too.This approach does mean a new front pulley assembly will be required, but this is in line with my philosophy of not damaging OEM stock when creating modified components. All the wearing surfaces are also easily replaced in years to come, and readily sourced, plus this system can recover worn timing covers.

Today, I managed to get the timing gear cover seal diameter surfaces measured on a Elaton Coordinate Measuring Machine, so I now have a very precise idea of what diameter I need to make the new part so that it has a nice interference fit. This is the complete crankshaft conversion kit assembly pictured below.

The grey part is the stainless steel seal carrier, and the cyan part the Viton seal. The yellow part is the steel inner ring, which is easily renewed if required, with the blue parts being the aluminium two piece front pulley components. These are located with a small dowel pin, however the parts are held together by the main front pulley crankshaft bolt.

It is necessary to make the parts this way to allow for DIY installations by Panhard owners, and it will be relatively straight forward to fit the conversion kit.

The picture below shows the optional trigger wheel version, which is needed by modern ignition or engine management systems, but fitting these is not for the faint hearted!

There are different tooth patterns available, but the one in the picture above is a 60-2 trigger wheel, commonly used by Bosch for VAG engines.

Panhard oil filter variants

Sunday 01 July 2012 Filed in: Panhard Oil

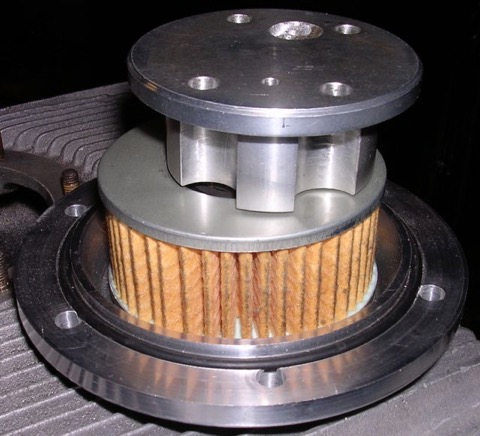

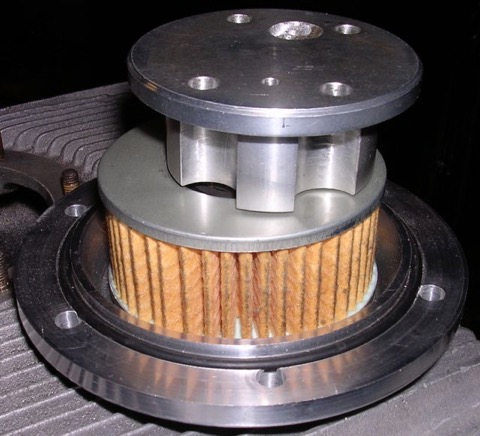

I was updating a few pages and noticed that one of the oil filter prototypes was wrongly labelled. I was doing a retrospective update after finding some photos on another MacBook, when something didn’t add up, and it turned out that I’d been investigating an internal filter variant, as the modified Renault Purflux filters were being discontinued. At this point in time, there were not many alternatives out there, so I was experimenting with internal paper cartridge filters, that I had seen in a local motor factor, and I made a prototype based on my original baseplate.

However with hindsight, it was a red herring, because a few weeks later I found a Mann Hummel external filter, that was better than the Purflux derived Renault unit, but the internal solution still has merit, especially in a double sump increased oil capacity format, which is a necessity to reduce the engine oil temperatures and increase the oil quality.

After looking at this some more, I have decided to remanufacture this variant, as it offers a different solution for the factory Panhard car, and can be used with double sump versions too. It does not hang down as far as the cartridge, which is important because the ground clearance under the engine is reduced by 50mm after fitting the factory double sump. The actual ground clearance doesn’t change however, but fitting a sump or a cartridge filter appears to lower it in some peoples’ eyes.

Further plus points are, a magnetic sump plug can also be incorporated into the sump plate if required, the filter is freely available from motor factors in Europe, and the oil filter cartridge doesn’t need to be modified, which simplifies things further for the less dextrous. Technically it’s also easier for people to understand, as the paper filter is a straight swap for the original mesh filter, although the low flow rate & low pressure drop through a paper element principle still applies.

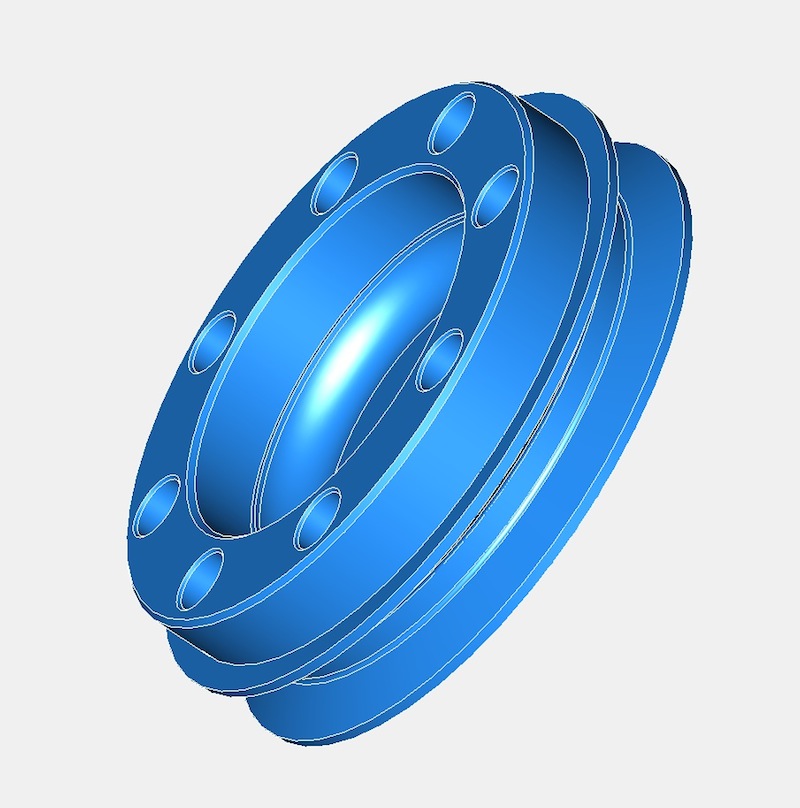

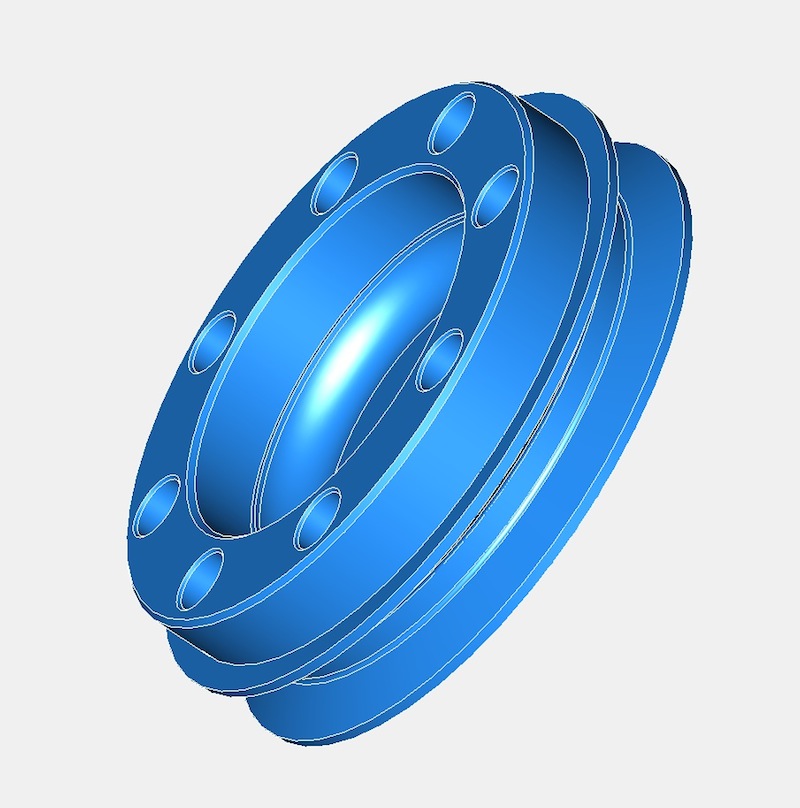

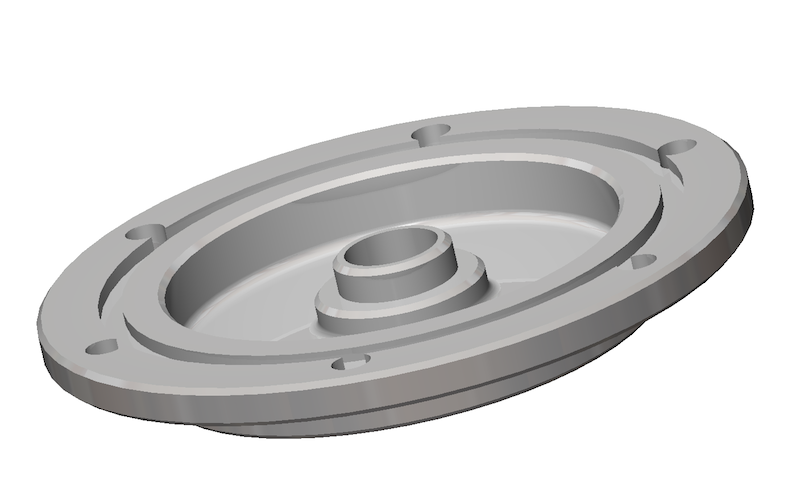

Latest CAD shown below, but it’s work in progress.

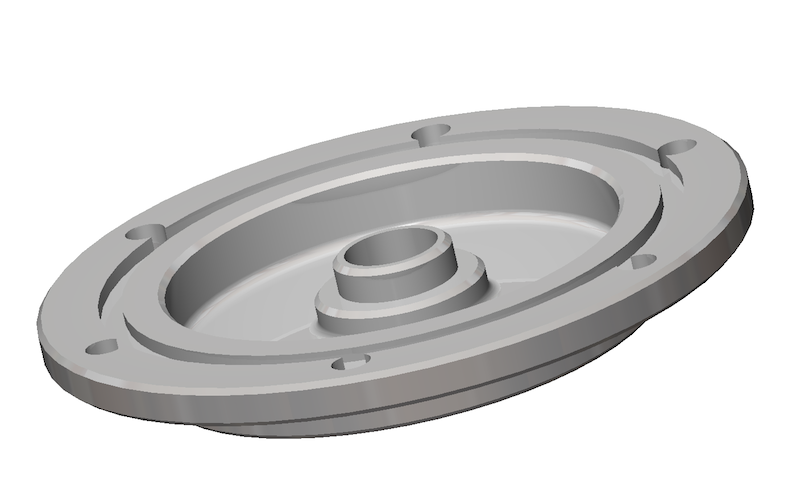

As I have been looking at the double sump variant for Brian Osbourne’s latest engine, it’s logical to try and use some of this for the next generation solution. I don’t have a double pump available at the moment, otherwise I would check whether I could use this new sump plate for the internal filter version with the double pump double sump application. I do know somebody with one, so I am going to take an internal filter and sump plate to their engine and see what is required, but it will have to wait until after the International Citröen Car Club 2012 Rally at Harrogate.

Latest thoughts in CAD for the double sump version, but only using the original oil pump, which is more than adequate assuming the crankcase oil circuits are modified. This version has a different pick up pipe and a flat not dished sump plate, so it will need two new parts.

However with hindsight, it was a red herring, because a few weeks later I found a Mann Hummel external filter, that was better than the Purflux derived Renault unit, but the internal solution still has merit, especially in a double sump increased oil capacity format, which is a necessity to reduce the engine oil temperatures and increase the oil quality.

After looking at this some more, I have decided to remanufacture this variant, as it offers a different solution for the factory Panhard car, and can be used with double sump versions too. It does not hang down as far as the cartridge, which is important because the ground clearance under the engine is reduced by 50mm after fitting the factory double sump. The actual ground clearance doesn’t change however, but fitting a sump or a cartridge filter appears to lower it in some peoples’ eyes.

Further plus points are, a magnetic sump plug can also be incorporated into the sump plate if required, the filter is freely available from motor factors in Europe, and the oil filter cartridge doesn’t need to be modified, which simplifies things further for the less dextrous. Technically it’s also easier for people to understand, as the paper filter is a straight swap for the original mesh filter, although the low flow rate & low pressure drop through a paper element principle still applies.

Latest CAD shown below, but it’s work in progress.

As I have been looking at the double sump variant for Brian Osbourne’s latest engine, it’s logical to try and use some of this for the next generation solution. I don’t have a double pump available at the moment, otherwise I would check whether I could use this new sump plate for the internal filter version with the double pump double sump application. I do know somebody with one, so I am going to take an internal filter and sump plate to their engine and see what is required, but it will have to wait until after the International Citröen Car Club 2012 Rally at Harrogate.

Latest thoughts in CAD for the double sump version, but only using the original oil pump, which is more than adequate assuming the crankcase oil circuits are modified. This version has a different pick up pipe and a flat not dished sump plate, so it will need two new parts.

Panhard piston update

Monday 11 June 2012 Filed in: Panhard Piston

Just had an update from the piston company, and they have sent me a grainy picture of the piston part finished.

The underside still needs machining, and the barrelling etc is still to do, but it’ll give an idea of how much shorter & lighter the piston will be.

The underside still needs machining, and the barrelling etc is still to do, but it’ll give an idea of how much shorter & lighter the piston will be.

Panhard musings

Monday 07 May 2012 Filed in: Blog Comments

I collected another Panhard crankshaft the other day to true up and lock in place, as it’s definitely not running concentric. It looks like the crank has turned ever so slightly on the crank pins and has a rather eccentric wobble.

As I am doing another crankshaft repair for Brian, I thought I’d compare the two, and at least this new crank confirms the other is too long between the bearings. In the discussions I had with the owner, I was bemused that somebody can spend a lot of money on bodywork and then baulk at the price of an engine.

Any engine that is going to get reconditioned will cost far more than swapping out for another. Its inevitable that the economics of doing so are questionable, but when you are faced with an older engine that is flawed, you’d think that would push the argument towards reconditioning, instead of just making do with any lump to hand.

In the case of the Panhard flat twin, unless you mod the lubrication circuits and increase the oil capacity you will be forever into a rebuild cycle, as these engines have some basic design faults. Panhard never had the money to eradicate these deficiencies, and whereas the engine initially was well designed, its’ subsequent development (to combat service faults) by different Panhard employees was not up to scratch as they missed the basics.

Unfortunately, very few people can see this point of view, and they seem to think you have to look to Panhards’ homeland for the best solutions, but there are no boundaries to good engineering or design. The UK has been a hub of motorsport development ever since Panhard started on their slippery slope to closure, and during this period British companies have seen dominance in World Rally cars and Formula 1. All this activity spins down to the lowest forms of motorsport, such as karting and clubman racing, and is also reflected in specialist educational courses available at the universities.

Nobody is suggesting that Panhards need F1 technology, but the companies that make parts for this industry have a huge expertise in material technology and manufacturing that can be applied to our engines, but only if you are open minded.

I hope over the next few months to surprise at least one person with the things I am working on, drop me a line if you are interested too.

As I am doing another crankshaft repair for Brian, I thought I’d compare the two, and at least this new crank confirms the other is too long between the bearings. In the discussions I had with the owner, I was bemused that somebody can spend a lot of money on bodywork and then baulk at the price of an engine.

Any engine that is going to get reconditioned will cost far more than swapping out for another. Its inevitable that the economics of doing so are questionable, but when you are faced with an older engine that is flawed, you’d think that would push the argument towards reconditioning, instead of just making do with any lump to hand.

In the case of the Panhard flat twin, unless you mod the lubrication circuits and increase the oil capacity you will be forever into a rebuild cycle, as these engines have some basic design faults. Panhard never had the money to eradicate these deficiencies, and whereas the engine initially was well designed, its’ subsequent development (to combat service faults) by different Panhard employees was not up to scratch as they missed the basics.

Unfortunately, very few people can see this point of view, and they seem to think you have to look to Panhards’ homeland for the best solutions, but there are no boundaries to good engineering or design. The UK has been a hub of motorsport development ever since Panhard started on their slippery slope to closure, and during this period British companies have seen dominance in World Rally cars and Formula 1. All this activity spins down to the lowest forms of motorsport, such as karting and clubman racing, and is also reflected in specialist educational courses available at the universities.

Nobody is suggesting that Panhards need F1 technology, but the companies that make parts for this industry have a huge expertise in material technology and manufacturing that can be applied to our engines, but only if you are open minded.

I hope over the next few months to surprise at least one person with the things I am working on, drop me a line if you are interested too.

Panhard Ignition Prototypes

Sunday 08 April 2012 Filed in: Panhard Ignition

I have had a nice update from Peter Breed, who says his ignition prototype is looking good. This will be a switchable two curve fully electronic set up that will be contained within the OEM distributor.

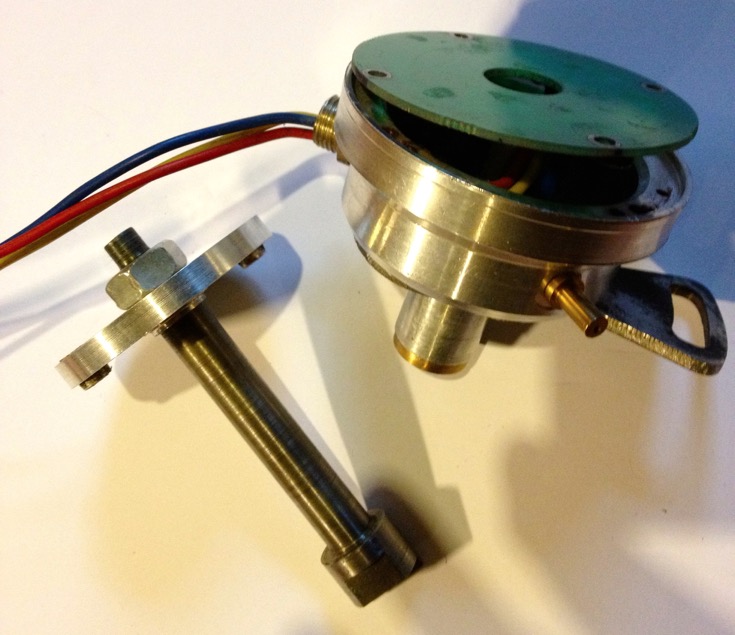

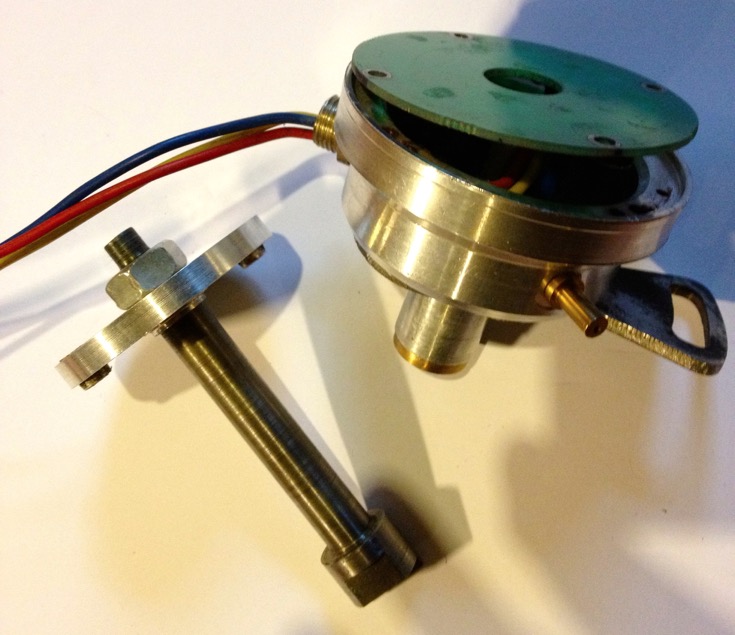

Like I said previously, I made several prototype ignitions in 2002, but the existing distributor couldn’t be used as it was too small a diameter to fit the circular board. My ignition prototypes were based on a 123ignition unit, sold as a Citröen 2CV Formula Bleu kit, pictured below, which incidentally was supplied by Ron Tyrrell.

I soon made an adaptor to take the standard 2CV unit, as well as a new driveshaft complete with magnets, body shown below.

There is a big problem with this set up, as the circuits design rotation is the wrong way for the engine, which incidentally was a stumbling block for 123 designers at the time too. Fortunately I realised if I flipped the board the magnetic field would pass through the circuit board and the rotation would be effectively reversed, so I made a new model to test the idea, which was just a spacer sandwiched between the two previous halves, and a new spindle to take the magnets.

Now the board and magnets were in the base not the lid like with the 2CV set up, and also the 123 lid wasn’t needed. I had to put a bearing in the top, to stop the wobble about the spindle, so I ended up with a rather large lump initially.

It wasn’t really surprising it ended up so large, but whereas I was making a conversion unit for the 123ignition kit before, I now had an opportunity to explore other options, and just use the basic component board.

So having tested the set up made a spark, using my motorised ignition rig, I made a new prototype, that ended being another version a couple of days later, but at least it was getting smaller. I incorporated the original 123 vacuum advance pick up into this version too, but the biggest drawback was I would have to up the ante again to fit the rev counter drive.

I wasn’t able to cut a gear drive for the tachometer drive like the SEV distributor needed and the economics were such that it wash’t viable to continue as it couldn’t meet the affordable target price.

Still it was starting to look a lot more designed, and this is were I left off about 9 years ago.

After the unit developed an electrical glitch, it was placed in a bag and left to gather dust, but by then the ignitions had taken a different turn with my MicroSquirt DIY EFI developments for the GTS1000. I would probably still retain the distributor for the tachometer drive, but use crankshaft based triggering off the front pulley, as it’s more precise and removes all the backlash and slop in the existing set up, which uses two sets of gears and two dog drives just to get to the contact breaker cam.

Interestingly, it has taken this long for 123ignitions to develop a smaller circuit board, but in the meantime they have developed a huge host of distributor based products for the more popular models out there, and these are quality products. I notice they have started to develop a DIY programmable interface for some of their products, but I don’t see any mention of the multispark set up one of the guys at 123 was working on at the time of my involvement.

Like I said previously, I made several prototype ignitions in 2002, but the existing distributor couldn’t be used as it was too small a diameter to fit the circular board. My ignition prototypes were based on a 123ignition unit, sold as a Citröen 2CV Formula Bleu kit, pictured below, which incidentally was supplied by Ron Tyrrell.

I soon made an adaptor to take the standard 2CV unit, as well as a new driveshaft complete with magnets, body shown below.

There is a big problem with this set up, as the circuits design rotation is the wrong way for the engine, which incidentally was a stumbling block for 123 designers at the time too. Fortunately I realised if I flipped the board the magnetic field would pass through the circuit board and the rotation would be effectively reversed, so I made a new model to test the idea, which was just a spacer sandwiched between the two previous halves, and a new spindle to take the magnets.

Now the board and magnets were in the base not the lid like with the 2CV set up, and also the 123 lid wasn’t needed. I had to put a bearing in the top, to stop the wobble about the spindle, so I ended up with a rather large lump initially.

It wasn’t really surprising it ended up so large, but whereas I was making a conversion unit for the 123ignition kit before, I now had an opportunity to explore other options, and just use the basic component board.

So having tested the set up made a spark, using my motorised ignition rig, I made a new prototype, that ended being another version a couple of days later, but at least it was getting smaller. I incorporated the original 123 vacuum advance pick up into this version too, but the biggest drawback was I would have to up the ante again to fit the rev counter drive.

I wasn’t able to cut a gear drive for the tachometer drive like the SEV distributor needed and the economics were such that it wash’t viable to continue as it couldn’t meet the affordable target price.

Still it was starting to look a lot more designed, and this is were I left off about 9 years ago.

After the unit developed an electrical glitch, it was placed in a bag and left to gather dust, but by then the ignitions had taken a different turn with my MicroSquirt DIY EFI developments for the GTS1000. I would probably still retain the distributor for the tachometer drive, but use crankshaft based triggering off the front pulley, as it’s more precise and removes all the backlash and slop in the existing set up, which uses two sets of gears and two dog drives just to get to the contact breaker cam.

Interestingly, it has taken this long for 123ignitions to develop a smaller circuit board, but in the meantime they have developed a huge host of distributor based products for the more popular models out there, and these are quality products. I notice they have started to develop a DIY programmable interface for some of their products, but I don’t see any mention of the multispark set up one of the guys at 123 was working on at the time of my involvement.

Panhard piston design finalised

Saturday 07 April 2012 Filed in: Panhard Piston

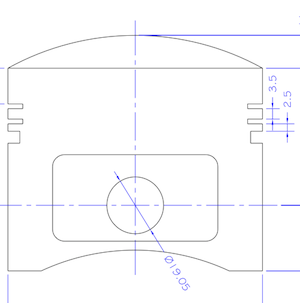

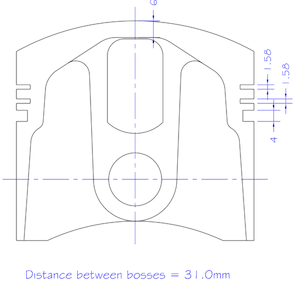

This is the latest iteration of the high compression Panhard piston that I am having made for Brian’s engine, and it will be substantially lighter than the OEM set up, but there is a slight compromise with the weight, because I want to use the standard cylinder and liner positions.

This piston will be used to modernise & improve the standard flat twin engine, and be a suitable replacement for the majority of the air cooled Panhard engines. It will need a new piston pin bush to cater for the standard crankshaft, but this is required whatever parts are fitted to the engine, as the original set up leaves little to be desired. This piston set will include a fully floating pin with improved lubrication to the piston pin bosses via cross drillings from the behind the oil control ring.

As the piston offers a higher compression over standard, I will be making some conversion shims to lower this for owners that want to run the standard ignition & carburation.

The new bore size will be 85.51mm, and the capacity will now be 861 cc, but if you want to play with different combinations, I created an engine size calculator here

Panhard pistons - order placed

Saturday 24 March 2012 Filed in: Panhard Piston

Over the last week, I managed to speak to the piston people, and what an engaging process that was. I started with a set idea in my head, and I really thought I knew what I wanted and then due to the limitations of the top ring to sleeve distance, the high compression or deck height of the standard set and the need for simplicity in installation, I had to go a different route.

As I discussed earlier, you can make anything work, but I wanted to avoid this. Pistons can be made in three ways, casting, forging and CNC from solid, but there are cost and number implications along the way. There are insufficient numbers to make a casting, and CNC from solid is double the expense of a machined forging, because it spends more time in the CNC machine, and has higher CAD/CAM costs. So that leaves forging and machining as the most suitable choice, but only if you can use an existing forging.

Panhard engines belong to an older generation of engine design, because nowadays you look to minimise surface areas in pistons and combustion chambers, which means domed pistons and hemispherical chambers are out. The implications for the forgings blanks are that most modern engine pistons do not have the large compression heights, and the top ring to compression height is minimised to reduce detonation, so the forgings are too small. The other thing is the bore size is slightly unusual, so you are generally looking at imperial forgings if you want to reuse the same liners.

The closest possible match to the Panhard piston on paper is a Royal Enfield Bullet piston, and that is what I thought I would be using, but it wasn’t after talking to the piston guru. I knew it was too heavy at over 600g complete, and so didn’t meet the weight targets, but I thought a little tweak here and there would sort that. It turns out it is unsuitable with the Panhard liner, and although it is good enough for a Royal Enfield, it isn’t for us.

It turns out when you look for a suitable forging, you look at the inside not the outside first, because if you want an intrinsically good design and therefore light as possible, the inner forging profile must match or follow the outer profile requirements closely, and believe it or not the original cast Panhard piston does this already. Now the selection is starting to get more focussed, so all that is really needed is a suitable forging with a domed inner profile, and enough room for the top ring detail. At this point I had to leave the meeting, because the piston designer had to look at the forging blanks in the old store. When I got back, it was really fortunate the company has been in business for 40 years, and had saved examples of the 320 forgings tools they had stored, because he found several pistons he thought might be suitable.

A short discussion later, and the choices were reduced to just one, and I just needed to confirm the dimensions in an email, so that production could be started. When I got home I burretted the combustion chamber and subtracted the piston dome volume, and worked backwards to get a higher compression version. This can always be reduced by shimming, like the original system, however I’ll be using new laser cut shims to vary the compression ratio. The 2012 engine will have a higher compression ratio, to make the more modern ring design work effectively. The latter is the limiting factor for the final rebore dimension, as it will be an existing imperial oversize set that I’ll be using. Incidentally, the oil supply for the piston pin will come off the liner walls and lubricate the piston pin via the oil control ring drillings.

As it is the start of the race season there is now a 12 week lead time, instead of the listed 8 weeks, and so today I placed an order for 12 pistons, which is six sets. This is a special developmental batch and it has a one off early adopter price, but the next batch will cost more at around £350 a set. There will need to be a piston pin or gudgeon pin conversion bush made to fit the standard rod, which varies anyway depending on the engine, that will add a little more cost to the total required. Any standard cylinder liners can be reused as they are over bored to a new controlled size. The pistons are expected to be available around the 18 June 2012. More details and pictures to be added later, but the piston is similar to this, without the valve pockets and with a smaller pin diameter.

There is no doubt in my mind, over the next few batches a truly modern Panhard piston will be developed. One of the most important elements for me, is the company will continually refine the design when they receive used examples by modifying the machining incrementally. This will reduce the wear characteristics, and allows for smaller piston to cylinder liner clearances to be used and also maintain the correct clearances when hot, which brings further improvements, but the piston becomes tailored to the engine combustion processes.

This fits in with my philosophy of creating a remanufactured standard engine, that incorporates modern thinking, increases reliability, and as an added bonus, additional performance improvement too. As this work involves an engine rebuild, it would be foolish not to incorporate the other benefits I have found over the years, and this fits well with a staged development program.

Obviously this depends on what the car is being used for and/or the individual views of the owner, and it’s basically a debate about keeping original no matter what, or improving on originality, so that it can be used today. Whatever your views, or standpoint the Panhard engine is not reliable by modern day standards, and is a ticking time bomb if you own one without knowing its’ condition. For people that use their cars, you must as a general rule, no matter what side of the fence you sit...

1. Improve the oil capacity and filtration, and protect what you have.

2. Look at the crankshaft sometime, preferably rebuild it using the Peter Breed system, but definitely reduce the original crankshaft loadings by fitting lightweight pistons.

3. If you fit lightweight pistons, you should get the cylinder induction ported to reduce reversion, which counteracts the original fuelling variations and makes for smoother everyday running. I would also recommend an annealed copper gasket at the inlet manifold joint aka Peter Breed.

4. Improve the ignition timing, by fitting a modern full electronic ignition system and twin plug the head. This will improve starting, the main ignition events, and reduce the likelihood of marginal combustion triggering pinking, detonation or worst case holed pistons.

It is no coincidence that I am developing products to fit these stages, and the pistons are first to be announced as they have the longest lead time. All will be seen on the 2012 engine, which although it will look like a standard engine to most eyes, it will be totally re-engineered under the skin for use in modern day traffic (including the annual bash around Monthléry).

As I discussed earlier, you can make anything work, but I wanted to avoid this. Pistons can be made in three ways, casting, forging and CNC from solid, but there are cost and number implications along the way. There are insufficient numbers to make a casting, and CNC from solid is double the expense of a machined forging, because it spends more time in the CNC machine, and has higher CAD/CAM costs. So that leaves forging and machining as the most suitable choice, but only if you can use an existing forging.

Panhard engines belong to an older generation of engine design, because nowadays you look to minimise surface areas in pistons and combustion chambers, which means domed pistons and hemispherical chambers are out. The implications for the forgings blanks are that most modern engine pistons do not have the large compression heights, and the top ring to compression height is minimised to reduce detonation, so the forgings are too small. The other thing is the bore size is slightly unusual, so you are generally looking at imperial forgings if you want to reuse the same liners.

The closest possible match to the Panhard piston on paper is a Royal Enfield Bullet piston, and that is what I thought I would be using, but it wasn’t after talking to the piston guru. I knew it was too heavy at over 600g complete, and so didn’t meet the weight targets, but I thought a little tweak here and there would sort that. It turns out it is unsuitable with the Panhard liner, and although it is good enough for a Royal Enfield, it isn’t for us.

It turns out when you look for a suitable forging, you look at the inside not the outside first, because if you want an intrinsically good design and therefore light as possible, the inner forging profile must match or follow the outer profile requirements closely, and believe it or not the original cast Panhard piston does this already. Now the selection is starting to get more focussed, so all that is really needed is a suitable forging with a domed inner profile, and enough room for the top ring detail. At this point I had to leave the meeting, because the piston designer had to look at the forging blanks in the old store. When I got back, it was really fortunate the company has been in business for 40 years, and had saved examples of the 320 forgings tools they had stored, because he found several pistons he thought might be suitable.

A short discussion later, and the choices were reduced to just one, and I just needed to confirm the dimensions in an email, so that production could be started. When I got home I burretted the combustion chamber and subtracted the piston dome volume, and worked backwards to get a higher compression version. This can always be reduced by shimming, like the original system, however I’ll be using new laser cut shims to vary the compression ratio. The 2012 engine will have a higher compression ratio, to make the more modern ring design work effectively. The latter is the limiting factor for the final rebore dimension, as it will be an existing imperial oversize set that I’ll be using. Incidentally, the oil supply for the piston pin will come off the liner walls and lubricate the piston pin via the oil control ring drillings.

As it is the start of the race season there is now a 12 week lead time, instead of the listed 8 weeks, and so today I placed an order for 12 pistons, which is six sets. This is a special developmental batch and it has a one off early adopter price, but the next batch will cost more at around £350 a set. There will need to be a piston pin or gudgeon pin conversion bush made to fit the standard rod, which varies anyway depending on the engine, that will add a little more cost to the total required. Any standard cylinder liners can be reused as they are over bored to a new controlled size. The pistons are expected to be available around the 18 June 2012. More details and pictures to be added later, but the piston is similar to this, without the valve pockets and with a smaller pin diameter.

There is no doubt in my mind, over the next few batches a truly modern Panhard piston will be developed. One of the most important elements for me, is the company will continually refine the design when they receive used examples by modifying the machining incrementally. This will reduce the wear characteristics, and allows for smaller piston to cylinder liner clearances to be used and also maintain the correct clearances when hot, which brings further improvements, but the piston becomes tailored to the engine combustion processes.

This fits in with my philosophy of creating a remanufactured standard engine, that incorporates modern thinking, increases reliability, and as an added bonus, additional performance improvement too. As this work involves an engine rebuild, it would be foolish not to incorporate the other benefits I have found over the years, and this fits well with a staged development program.

Obviously this depends on what the car is being used for and/or the individual views of the owner, and it’s basically a debate about keeping original no matter what, or improving on originality, so that it can be used today. Whatever your views, or standpoint the Panhard engine is not reliable by modern day standards, and is a ticking time bomb if you own one without knowing its’ condition. For people that use their cars, you must as a general rule, no matter what side of the fence you sit...

1. Improve the oil capacity and filtration, and protect what you have.

2. Look at the crankshaft sometime, preferably rebuild it using the Peter Breed system, but definitely reduce the original crankshaft loadings by fitting lightweight pistons.

3. If you fit lightweight pistons, you should get the cylinder induction ported to reduce reversion, which counteracts the original fuelling variations and makes for smoother everyday running. I would also recommend an annealed copper gasket at the inlet manifold joint aka Peter Breed.

4. Improve the ignition timing, by fitting a modern full electronic ignition system and twin plug the head. This will improve starting, the main ignition events, and reduce the likelihood of marginal combustion triggering pinking, detonation or worst case holed pistons.

It is no coincidence that I am developing products to fit these stages, and the pistons are first to be announced as they have the longest lead time. All will be seen on the 2012 engine, which although it will look like a standard engine to most eyes, it will be totally re-engineered under the skin for use in modern day traffic (including the annual bash around Monthléry).

Panhard pistons - a quick overview

Sunday 11 March 2012 Filed in: Panhard Piston

Panhard pistons are quite heavy and bulky items compared to their modern day equivalents, because the piston has to be domed to make the compression high enough within the hemispherical combustion chamber in the Panhard engine.

The biggest limiting factor is the close proximity of the top ring to the end of the steel liner, and because the top ring is quite far down the piston, around 10mm from the top deck, this really limits what pistons you can use. BMW R80 non Nicasil, circa 1980’s, can be used, but they are very scarce, as most people fit the 1000cc conversion kits, as they are cheaper. You can also get a piston from Peter Breed, which is a forged American item. Others that can be used are various Italian, German, American & British designs, but nearly all require a little rework to the cylinders to overcome the cylinder liner problem.

What do the standard pistons look like? Here’s the troublesome liner position, and it’s about 1.5mm from the top ring…this pic is taken from a cutaway section.

These engines were from the junk pile, but they still have their uses, as the piston below was cut up to show the typical cross-sectional areas that exist within the original. There are more than one type of Panhard piston used in the flat twin engine, but this is the later 4 ringed type.

Why is this done? I need to understand why the naked Panhard piston weighs 505 grams, when my achievable target weight for a heavily domed piston should be sub 400grams, which for example is double the weight of a single cylinder Supermotard piston from 2002, and probably three times heavier than a complete MotoGP piston! However, pistons that light do have very short maintenance cycles, which are measured in hours not years.

Panhard crankcase rear bearing support

Saturday 10 March 2012 Filed in: Panhard Oil

I was going to remove the rear NU209 main bearing on the engine, but needed to make a small adaptor to measure the end float on the crankshaft before I do so. This particular engine has a little bit of movement in the rear crank pin, and I need to find out why it has moved.

Historically the engines have had gradual tweaks over their lifetime, and the rear main bearing support plate which bolts to the crankcase is no exception. The first ones were aluminium, and the later ones were cast iron with a flexible lipped seal, as opposed to a steel piston ring. Oil starvation and inadequate capacity have always been an issue, as the cars were introduced to the ever increasing demands of modern day traffic, and I spotted another tweak today.

The early M6 back plate is on the left and the later M8 is on the right, and can you spot the difference?

The answer is the holes are bigger on the later one, which means more oil can be supplied to the rear bearing. After measuring these it equates to an improvement of 15% over the earlier design.

Historically the engines have had gradual tweaks over their lifetime, and the rear main bearing support plate which bolts to the crankcase is no exception. The first ones were aluminium, and the later ones were cast iron with a flexible lipped seal, as opposed to a steel piston ring. Oil starvation and inadequate capacity have always been an issue, as the cars were introduced to the ever increasing demands of modern day traffic, and I spotted another tweak today.

The early M6 back plate is on the left and the later M8 is on the right, and can you spot the difference?

The answer is the holes are bigger on the later one, which means more oil can be supplied to the rear bearing. After measuring these it equates to an improvement of 15% over the earlier design.

Panhard crankcase front oil drilling modifications

Sunday 04 March 2012 Filed in: Panhard Oil

The original engines had this oil feed visible above the camshaft bore at the very front of the crankcase, which is shown below. As the camshaft rotates this drilling is filled two times per camshaft revolution, and after this it passes in a trough that is underneath the bearing and the oil jumps into the slingers. Some oil splashes back and passes through the main bearing, but the rest is accelerated by the slingers at the crank web, and passes through the big end bearing via a drilling in the crank web before exiting and splash lubricating the little end.

Unfortunately this hole is too small, and it is the cause of a 50% reduction in flow rate over the rear pro rata. There is an added complication that this hole is also 50% smaller than the rear oil feed, so there is quite a bit of reduction in potential flow rate assuming the pressures were the same. As you might have read there is a pressure difference, because of the secondary drilling that fed the camshaft timing gear on the early engines which compounded the problem , and led to reliability issues, which eventually forced an engine redesign to this area.

This can be negated by carrying out a few modifications, all of which will be documented here.

It might not be obviously apparent from this picture, but the hole size is now 6mm diameter, whereas the one above is just 4mm. This new oil feed now matches the camshaft aperture, so all openings, front and rear are timed equally. The 4mm diameter hole in the middle that is drilled presently, will have to be enlarged to 5mm to match the rear oil feed that is fed from the common camshaft oil gallery. At first it is more important to get the hole in the right position, and work from this, which is why it is now at 5mm diameter, as shown below.

This now means both front and rear oil galleries are equally phased and have the same pressure variations, as there is no mismatched timing gear oil feed anymore affecting the front oil supply. However that still leaves the task of creating a new oil feed to do this, because you didn’t think the gear was going to lubricate itself from the plain bearing leaking, but that’ll be another update.

Unfortunately this hole is too small, and it is the cause of a 50% reduction in flow rate over the rear pro rata. There is an added complication that this hole is also 50% smaller than the rear oil feed, so there is quite a bit of reduction in potential flow rate assuming the pressures were the same. As you might have read there is a pressure difference, because of the secondary drilling that fed the camshaft timing gear on the early engines which compounded the problem , and led to reliability issues, which eventually forced an engine redesign to this area.

This can be negated by carrying out a few modifications, all of which will be documented here.

It might not be obviously apparent from this picture, but the hole size is now 6mm diameter, whereas the one above is just 4mm. This new oil feed now matches the camshaft aperture, so all openings, front and rear are timed equally. The 4mm diameter hole in the middle that is drilled presently, will have to be enlarged to 5mm to match the rear oil feed that is fed from the common camshaft oil gallery. At first it is more important to get the hole in the right position, and work from this, which is why it is now at 5mm diameter, as shown below.

This now means both front and rear oil galleries are equally phased and have the same pressure variations, as there is no mismatched timing gear oil feed anymore affecting the front oil supply. However that still leaves the task of creating a new oil feed to do this, because you didn’t think the gear was going to lubricate itself from the plain bearing leaking, but that’ll be another update.

Panhard crankcase camshaft drive gear oil level

Sunday 04 March 2012 Filed in: Panhard Oil

A little mod that improves oil quality, reduces heat build up in the oil, and improves pumping losses to the engine. At the moment the Panhard timing case oil level is determined by the hi level drainage points shown here or leaking past the front main bearing.

Normal practice for a splash lubricated gear is to have no more than a third of the overall gear diameter immersed, so why Panhard did this surprises me. Originally they had a fibre wheel of massive proportions meshing to a hardened steel gear, with huge gear area, and in all fairness it probably didn’t need much lubrication. If it was being made today this fibre wheel, which is often replaced by an aluminium one, could be made of a plastic material quite easily.

These new drillings, now restore the status quo, and at the same time allow for this area to get some oil changes. Technically these wouldn’t get fully drained, unless you remove the steel timing cover case, because there is no low level return point. I think it is realistic to revise this mod and lower the oil level further, but as this is the third engine I have modded in this area, I will wait until I get some better feedback before doing so.

Normal practice for a splash lubricated gear is to have no more than a third of the overall gear diameter immersed, so why Panhard did this surprises me. Originally they had a fibre wheel of massive proportions meshing to a hardened steel gear, with huge gear area, and in all fairness it probably didn’t need much lubrication. If it was being made today this fibre wheel, which is often replaced by an aluminium one, could be made of a plastic material quite easily.

These new drillings, now restore the status quo, and at the same time allow for this area to get some oil changes. Technically these wouldn’t get fully drained, unless you remove the steel timing cover case, because there is no low level return point. I think it is realistic to revise this mod and lower the oil level further, but as this is the third engine I have modded in this area, I will wait until I get some better feedback before doing so.

Panhard oil pump output

Sunday 04 March 2012 Filed in: Panhard Oil

I have mentioned earlier that the Panhard oil supply was designed to be a low flow, low oil pressure system, but I haven’t really explained why.

Originally the engine had a lot of roller bearings inside it, and crucially the crankshaft was suspended using these. In fact cylindrical roller bearing set ups are making a come back in engine design, especially in the USA where Timken are applying this to some current engines, to showcase the technology again, and also promote their own bearing interests. One of the reasons they are using it, is to reduce pumping losses, and the frictional drag reductions against the more common plain bearing engines, because there is an environmental need to make combustion engines more economical.

The Panhard engine was quite clever in that it used a small pump to get the oil roughly where it was needed, and then the centrifugal effect of the slingers in the crankshaft webs gave a speed related response to the engine needs. This was a good fit with the requirements of the engine, and although there was a maintenance issue with slingers clogging up, mileages were not great in the late 1940’s when the engine was being designed, and a 30,000 mile target wasn’t unreasonable. Fast forward to the 21st Century and maybe some things would be different now, and if you look at the evolution of a similar engine, the BMW R50 motorcycle, that moved from centrifugal oil supply to a cross drilled crank, and the more common one piece crankshaft & split connecting rods with plain bearings.

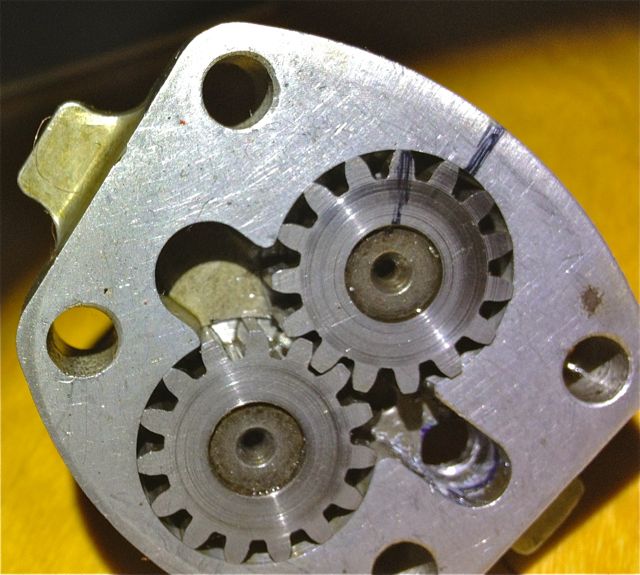

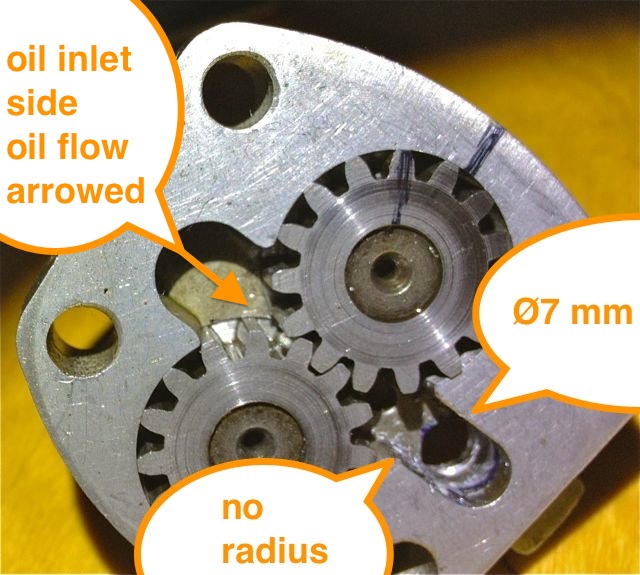

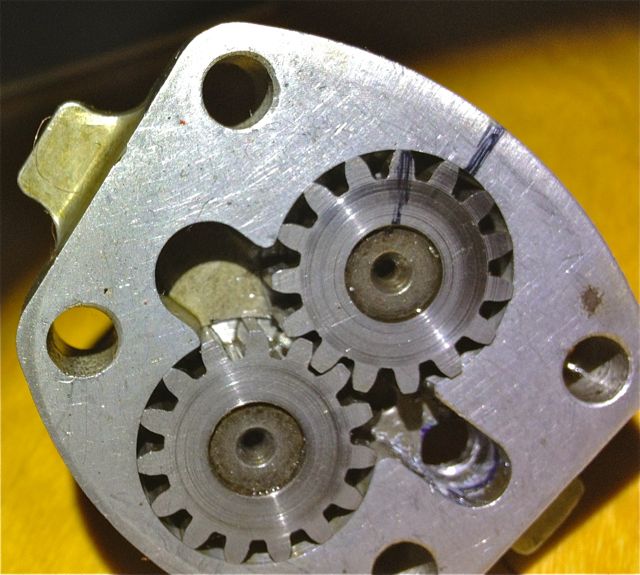

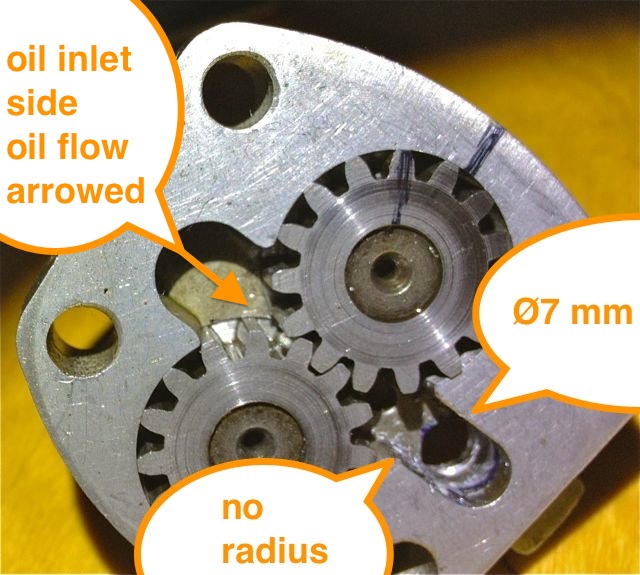

Aside from the maintenance issue with the slingers, there is nothing really wrong with the original oil pump, but if you read the history books you might be lead to believe otherwise. Here is the pump, and it is a gear type oil pump, which was a current design around the time, and it is more than adequate for the job. There are a couple of issues, that if it was being made today, that you would change, but I’ll elaborate later.The first one is, there are no rounded edges from the oil pump body into the output drilling, which is 90 degrees to it, and this will cause back pressure and cavitation, at higher oil volumes .

So if I was going to do one thing to address this, it would involve using a Dremel and doing this.

This modified oil pump will now flow more oil at speed, when you want it and there will be less bubbles in the oil as a result, which has the effect of improving the oil quality. I have successfully done this on three engines to date, and did test it out on the oil filter crankcase test rig many years ago. It is beneficial, and is one way of simply boosting the nett oil flow, but there is a bigger win win at the crankcase entry. If you were trying to maximise flow, you wouldn’t squeeze a garden hose pipe, but that’s exactly what Panhard did, because the crankcase oil inlet from the pump is 4.8mm diameter, yet the pump output is 7mm in diameter, which is almost a 50% reduction in cross sectional area. So after radiussing the outlet of the pump body there is an even bigger restriction downstream, and all the oil for the engine is fed by this small hole. It really doesn’t make sense with hindsight

You can see the small inlet pipe into the crankcase, and also see where the oil pump mates up to it, which is the black circle I have inked in and the centre of the outlet is represented by the black lines. So again the flexible shaft is used to reshape this area, and the important thing is to match the mating diameters more closely. It makes sense to machine and open up this drilling to match the oil pump, as this will increase the flow rate into the main oil galleries, and it has no effect on the pressure of the system, contrary to what you might think. The pressure in the unmodified camshaft is controlled by the cross drilling after this, and the cylinder head feeds likewise by the size of their respective openings too.

Crankcase main oil gallery modified to match oil pump outlet diameter.

Originally the engine had a lot of roller bearings inside it, and crucially the crankshaft was suspended using these. In fact cylindrical roller bearing set ups are making a come back in engine design, especially in the USA where Timken are applying this to some current engines, to showcase the technology again, and also promote their own bearing interests. One of the reasons they are using it, is to reduce pumping losses, and the frictional drag reductions against the more common plain bearing engines, because there is an environmental need to make combustion engines more economical.

The Panhard engine was quite clever in that it used a small pump to get the oil roughly where it was needed, and then the centrifugal effect of the slingers in the crankshaft webs gave a speed related response to the engine needs. This was a good fit with the requirements of the engine, and although there was a maintenance issue with slingers clogging up, mileages were not great in the late 1940’s when the engine was being designed, and a 30,000 mile target wasn’t unreasonable. Fast forward to the 21st Century and maybe some things would be different now, and if you look at the evolution of a similar engine, the BMW R50 motorcycle, that moved from centrifugal oil supply to a cross drilled crank, and the more common one piece crankshaft & split connecting rods with plain bearings.

Aside from the maintenance issue with the slingers, there is nothing really wrong with the original oil pump, but if you read the history books you might be lead to believe otherwise. Here is the pump, and it is a gear type oil pump, which was a current design around the time, and it is more than adequate for the job. There are a couple of issues, that if it was being made today, that you would change, but I’ll elaborate later.The first one is, there are no rounded edges from the oil pump body into the output drilling, which is 90 degrees to it, and this will cause back pressure and cavitation, at higher oil volumes .

So if I was going to do one thing to address this, it would involve using a Dremel and doing this.

This modified oil pump will now flow more oil at speed, when you want it and there will be less bubbles in the oil as a result, which has the effect of improving the oil quality. I have successfully done this on three engines to date, and did test it out on the oil filter crankcase test rig many years ago. It is beneficial, and is one way of simply boosting the nett oil flow, but there is a bigger win win at the crankcase entry. If you were trying to maximise flow, you wouldn’t squeeze a garden hose pipe, but that’s exactly what Panhard did, because the crankcase oil inlet from the pump is 4.8mm diameter, yet the pump output is 7mm in diameter, which is almost a 50% reduction in cross sectional area. So after radiussing the outlet of the pump body there is an even bigger restriction downstream, and all the oil for the engine is fed by this small hole. It really doesn’t make sense with hindsight

You can see the small inlet pipe into the crankcase, and also see where the oil pump mates up to it, which is the black circle I have inked in and the centre of the outlet is represented by the black lines. So again the flexible shaft is used to reshape this area, and the important thing is to match the mating diameters more closely. It makes sense to machine and open up this drilling to match the oil pump, as this will increase the flow rate into the main oil galleries, and it has no effect on the pressure of the system, contrary to what you might think. The pressure in the unmodified camshaft is controlled by the cross drilling after this, and the cylinder head feeds likewise by the size of their respective openings too.

Crankcase main oil gallery modified to match oil pump outlet diameter.

Panhard crankcase oil circulation faults (revisited)

Saturday 03 March 2012 Filed in: Panhard Oil

A quick history lesson on Panhard engine failures. The front main bearing and front cylinder crankshaft big end started to develop failures, as they increased the horsepower. It was attributed to insufficient oil supply, and so the front end lubrication was revised, and the camshaft timing gears were used as a splash lubrication system and the oil drilling that provided that role under the front main bearing was removed. This modification was introduced from around the early 1960’s, and ran to the end of production in 1967.

Unfortunately for Panhard they were barking up the wrong tree, despite the engine coming from a well thought out design originally, other people tinkered with the design knee jerk fashion as the problems developed, and nobody took an overview and look at the root causes. The financial woes and Citröen management probably didn’t help, but as Panhard died in 1967, we will never really know.

Flash forward to the next century, and if you are running one of these engines, it will almost be suffering from the result of this modification. As the engine ages the oil pump becomes more marginal, the priority oil fed valve gear bushes in the head wear, and the oil into the camshaft gallery reduces. Now the front bearings don’t really fatigue like they used to, but the rears suffer because they are pump related. So the problem has transferred itself, and the question that should be asked is why?

Of course if you look at the development of these engines you will read about the engines modified for endurance racing, which had higher capacity pumps, and an increased oil capacity with the fitment of an additional sump, that also acted as a baffled cavity for the oil pick up pipe. This subset of development has been an evolutionary branch of Panhard engine that needs revising, because if you really look at the problem, these solutions are papering over the cracks of a design fault. If you go back in time, and look at the engine design of the Panhard flat twin compared to others, there are numerous good points taken from lots of influences. The crankshaft oil supply is reminiscent of Bugatti & the early BMW motorcycle engines, but it is essentially a low pressure system, and even the design of the original plain bearing surfaces reflect this, so why fit a higher pressure set up, but that’s another story.

For example in the front bearing of the camshaft, which has a very large diameter at the front where the timing gear is driven by the crankshaft, and a more normal sized bearing diameter at the rear. Also, if you look at the oil drillings that feed these plain bearings, they are proportionately scaled to suit. The camshaft is the common denominator in all of this because it is one of three main oil feeds from the oil pump, and the supply conduit for the front and rear main bearings and the crankshaft lubrication, but wasn’t there a problem here?

So how can a central oil gallery that feeds both the front and rear crankshafts be at fault? Actually, the central gallery is not the problem, because the flow into this is separate from the outputs, and if you look at these, the problem is almost explained. The original designer knew he needed to equalise the distribution of the oil, so the oil outputs for the front and rear crankshaft feeds are phased to do just this, and as the cross drillings are on a rotating surface the timing window on the camshafts are scaled accordingly. However, although the rear crankshaft oil drilling is sized to match the rear camshaft drilling, the front is mismatched, because the oil drilling in the crankcase is too small.

On examination the oil drilling needs to be around 6mm diameter, when it is only 4mm, which is a 50% reduction in oil supply compared to the rear, and this alone would explain the front end failure susceptibility, but it doesn’t end there. The original designer tried to phase the oil supply to the front and rear ends equally, but somebody else decided the camshaft timing gear at the front should have some more lubrication, and put in an additional drilling. The reality was that the original plain bearing would have leaked into this cavity, and as there were no low level drainage holes, the oil wouldn’t go away, so it really didn’t need the additional drilling, but the biggest problem was where it was positioned. The oil pump doesn’t need to be big, as the engine only needed low flow rates and low pressure to work within it original design specifications, however any pressure drop say after a drilling would take a little time to recover, and this was accepted in the design layout, but as soon as the oil drilling to the front timing gear was placed ahead of the front end oil supply, the 50% reduction in flow rate all things being equal just got worse, as this drilling lost pressure after 60 degrees of a 90 degree recovery window, and only gave the camshaft 30 degrees to recover the oil pressure in the gallery. This means the front crankshaft oil feeds are compromised further, whereas the rears are unaffected, and it was all down to a simple production oversight.

What is the solution? Again, a quick history lesson will tell you all you need to know, and it is the route of many flat twin Panhard devotees, but don’t bother looking at the history books, what you have to do is engine specific, but that’ll be for another day. Suffice to say, I spotted this many years ago, and have been making parts and modding a few engines to overcome these oil related faults every time I get hold of one.

Unfortunately for Panhard they were barking up the wrong tree, despite the engine coming from a well thought out design originally, other people tinkered with the design knee jerk fashion as the problems developed, and nobody took an overview and look at the root causes. The financial woes and Citröen management probably didn’t help, but as Panhard died in 1967, we will never really know.

Flash forward to the next century, and if you are running one of these engines, it will almost be suffering from the result of this modification. As the engine ages the oil pump becomes more marginal, the priority oil fed valve gear bushes in the head wear, and the oil into the camshaft gallery reduces. Now the front bearings don’t really fatigue like they used to, but the rears suffer because they are pump related. So the problem has transferred itself, and the question that should be asked is why?

Of course if you look at the development of these engines you will read about the engines modified for endurance racing, which had higher capacity pumps, and an increased oil capacity with the fitment of an additional sump, that also acted as a baffled cavity for the oil pick up pipe. This subset of development has been an evolutionary branch of Panhard engine that needs revising, because if you really look at the problem, these solutions are papering over the cracks of a design fault. If you go back in time, and look at the engine design of the Panhard flat twin compared to others, there are numerous good points taken from lots of influences. The crankshaft oil supply is reminiscent of Bugatti & the early BMW motorcycle engines, but it is essentially a low pressure system, and even the design of the original plain bearing surfaces reflect this, so why fit a higher pressure set up, but that’s another story.